ODs’ role promising in detecting Alzheimer’s disease

Science is evolving, and practices will soon find themselves in a moral quagmire. Detection and clinical staging of AD using vision and ophthalmic imaging are close at hand.

More than 5 million Americans, 70 percent of all dementia patients, and their loved ones are currently living with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and that number is expected to rise to 16 million by 2050.1

There are two principal forms of Alzheimer’s disease:

• Early-onset primarily genetically-based disease accounting for only approximately 1 percent of all cases

• Late-onset primarily environmentally-influenced Alzheimer’s disease associated with the apo-E4 gene and generally starting after age 60.2

Previously from Dr. Richer: How zinc affects AMD

In early-onset AD, hundreds of mutations have been identified in three different genes. All mutations affect the metabolism of a sticky and aggregating short peptide known as the amyloid Ã-protein.3

The eye-brain nexus

The eye and brain share similar embryologic origins. AD also affects visual fields, eye movements, and pupil and optic nerve function.4 As ODs, we intimately examine the ocular-cerebral system daily. There is an intimate connection between amyloid Ã-protein found in AMD drusen, a type of peripheral cortical cataract, and AD pathology.5,6

Noninvasive imaging techniques have emerged that accurately and noninvasively detect and monitor amyloid deposition in the human lens and retina.4 For AD cataracts, a commercial device involving a fluorescent amyloid ligand eye drop and slit-lamp based detection system, has undergone clinical trials.7 AD Retinal imaging technology is also close at hand.8

Related: OD education must keep up with industry changes

Amyloid Ã-protein

The causes of late-onset AD are not well understood, and patients can develop amyloid plaques with or without succumbing to AD. More than 250 clinical trials have been conducted on a variety of amyloid cascade treatments-including several that can remove amyloid Ã-protein from the brain. All have failed to halt AD progression.2,9,10

Amyloid Ã-protein is a marker of AD but is not sufficient in itself to develop AD. Other biochemical and morphological features of AD. These features include altered calcium, phospholipid, cholesterol, and sugar metabolism, as well as mitochondrial dynamics and function that appear prior to plaque (amyloid) and tangle (Ï protein) accumulation.10

As ODs, we examine about one-third of the U.S. population yearly. Whether you are scientifically inclined to be an “amyloidist” or “tauist” (Ï protein), the clinical imperative is eliminating these oculo-cerebral toxins. This is accomplished by counseling patients on how to reduce environmental toxins such as sugar and prescribing nutrients for repair and maintenance of both the eyes and brain.

Canine dementia and AD

We know amyloid and Ï protein accumulation begins early in adult life, building up and gradually.2,10 Dogs develop “canine dementia’ similar to human AD.11

The best veterinary option to manage canine brain aging is correcting metabolic changes and eliminating risk factors associated with brain aging and dementia simultaneously via high-quality age-appropriate dog food.11

Related: How diet and nutrition affect disease

Veterinary science suggests that human late-onset AD can be prevented by implementing specific lifestyle changes and taking certain dietary supplements such as antioxidants, B-complex vitamins, cholesterol, and medium-chain triglycerides.11 One human AD foundation has endorsed a medical-food cocktail called Supplemem AD.12 This product is backed by two animal studies at the University of Kentucky.13,14

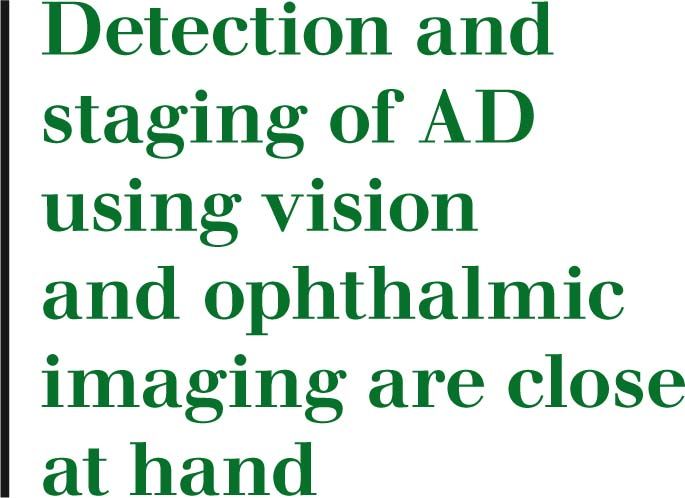

Both resveratrol (in red wine) and curcumin (in turmeric) have been found to benefit AD in basic science studies.15,16,17 Resveratrol addresses AD through 10 factors associated with the disease.15,16 (Figure 1)

Nutrition is most effective when combined with a daily action plan that includes activities that multi-dimensionally challenge the brain.2

Future of AD detection

Science is evolving, and practices will soon find themselves in a moral quagmire. Detection and clinical staging of AD using vision and ophthalmic imaging are close at hand.

Related: ODs must teach patients about proper nutrition

Yet current treatments target only the symptoms of AD, failing to halt disease pathology. AD detection protocols will be available years before new drugs due to long pharmaceutical lead times.

If we have found a solution for mice and senior dogs, then why not a solution for senior humans?

References

1. Alzheimer’s Association. 2017 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Available at: http://www.alz.org/facts/overview.asp. Accessed 11/10/17.

2. Alzheimer’s Disease Foundation. Alzheimer’s Disease 101. Available at: http://ad.foundation/alzheimers-information/. Accessed 11/10/17.

3. Giri M, Shah A, Upreti B, Rai JC. Unraveling the genes implicated in Alzheimer's disease. Biomed Rep. 2017 Aug;7(2):105-114.

4. Lim JK, Li QX, He Z, Vingrys AJ, Wong VH, Currier N, Mullen J, Bui B, Nguyen CT. The Eye As a Biomarker for Alzheimer's Disease. Front Neurosci. 2016 Nov 17;10:536.

5. Kerbage C, Sadowsky CH, Tariot PN, Agronin M, Alva G, Turner FD, Nilan D, Cameron A, Cagle GD, Hartung PD. Detectionion of Amyloid β Signature in the Lens and Its Correlation in the Brain to Aid in the Diagnosis of Alzheimer's Disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2015 Dec;30(8):738-45.

6. Biscetti L, Luchetti E, Vergaro A, Menduno P, Cagini C, Parnetti L. Associations of Alzheimer's disease with macular degeneration. Front Biosci (Elite Ed). 2017 Jan 1;9:174-191.

7. Kerbage C, Sadowsky CH, Jennings D, Cagle GD, Hartung PD. Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnosis by Detecting Exogenous Fluorescent Signal of Ligand Bound to Beta Amyloid in the Lens of Human Eye: An Exploratory Study. Front Neurol. 2013; 4: 62.

8. Koronyo Y, Biggs D, Barron E, Boyer DS, Pearlman JA, Au WJ, Kile SJ, Blanco A, Fuchs DT, Ashfaq A, Frautschy S, Cole GM, Miller CA, Hinton DR, Verdooner SR, Black KL, Koronyo-Hamaoui M. Retinal amyloid pathology and proof-of-concept imaging trial in Alzheimer’s disease. JCI Insight. 2017 Aug 17;2(16). pii: 93621.

9. Ricciarelli R, Fedele E. The Amyloid Cascade Hypothesis in Alzheimer's Disease: It's Time to Change Our Mind. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2017;15(6):926-935.

10. Area-Gomez E, Schon EA. Alzheimer Disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;997:149-156.

11. Pan Y. Enhancing brain functions in senior dogs: a new nutritional approach. Top Companion Anim Med. 2011 Feb;26(1):10-6.

12. Alzheimer’s Disease Foundation. Medical Food Cocktail. Available at: http://ad.foundation/medical-food-cocktail/. Accessed 11/10/17.

13. Parachikova A, Green KN, Hendrix C, LaFerla FM. Formulation of a medical food cocktail for Alzheimer’s disease: beneficial effects on cognition and neuropathology in a mouse model of the disease. PLoS One. 2010 Nov 17;5(11):e14015.

14. Head E, Murphey HL, Dowling AL, McCarty KL, Bethel SR, Nitz JA, Pleiss M, Vanrooyen J, Grossheim M, Smiley JR, Murphy MP, Beckett TL, Pagani D, Bresch F, Hendrix C. A combination cocktail improves spatial attention in a canine model of human aging and Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;32(4):1029-42.

15. Kou X, Chen N. Resveratrol as a Natural Autophagy Regulator for Prevention and Treatment of Alzheimer's Disease. Nutrients. 2017 Aug 24;9(9). pii: E927

16. Sawda C, Moussa C, Turner RS. Resveratrol for Alzheimer's disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2017 Sep;1403(1):142-149.

17. Tang M, Taghibiglou C. The Mechanisms of Action of Curcumin in Alzheimer's Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;58(4):1003-1016.