- Therapeutic Cataract & Refractive

- Lens Technology

- Glasses

- Ptosis

- AMD

- COVID-19

- DME

- Ocular Surface Disease

- Optic Relief

- Geographic Atrophy

- Cornea

- Conjunctivitis

- LASIK

- Myopia

- Presbyopia

- Allergy

- Nutrition

- Pediatrics

- Retina

- Cataract

- Contact Lenses

- Lid and Lash

- Dry Eye

- Glaucoma

- Refractive Surgery

- Comanagement

- Blepharitis

- OCT

- Patient Care

- Diabetic Eye Disease

- Technology

Know the four stages of dry eye blepharitis syndrome

New thoughts on managing anterior segment disease are prompting opportunities for a healthier ocular surface. The eyelid margin has been the focus of much research, and clinically we are appreciating the delicate balance that a healthy lid margin provides for the ocular surface. This has implications for both contact lens and non-contact lens wearers.

Rynerson and Perry proposed a new theory regarding blepharitis and its long-term effects to the health of the ocular surface called “dry eye blepharitis syndrome“ (DEBS).1

Related: Experts offer top blepharitis tips

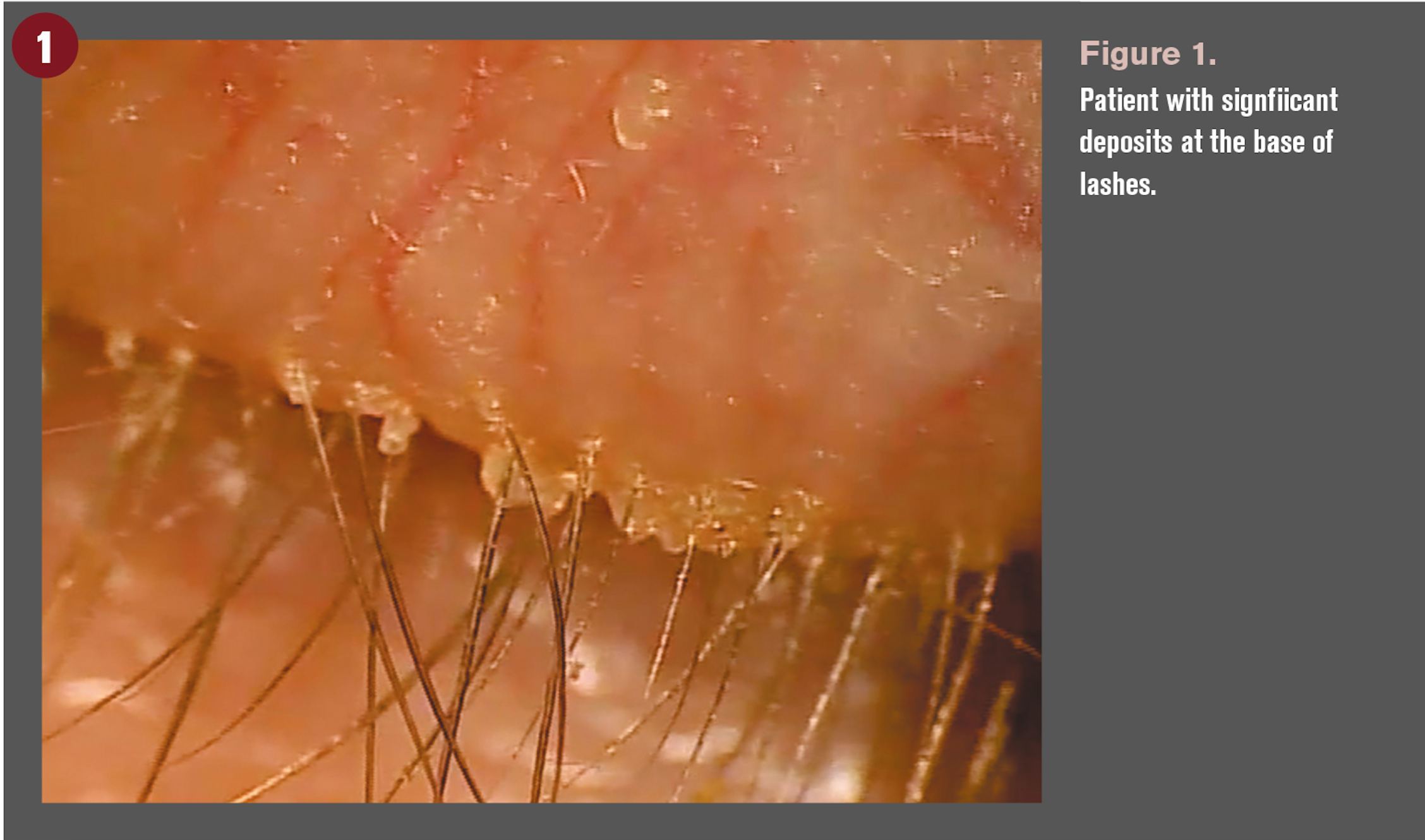

Clinically, we refer to a patient as having blepharitis by the presence of collarettes or deposits at the base of the lashes (Figure 1). Interestingly, they are a manifestation of blepharitis; ODs are at times guilty of not diagnosing based on the inflammatory state. Blepharitis, by definition, is an inflammation of the eyelid margin, and, therefore, using lid debris as an identifier of blepharitis falls short.

Rynerson and Perry discuss the overpopulation of bacteria creating biofilms over the lid margin surface as the major contributor to much of the downstream inflammation and, therefore, dry eye.

Bacteria and biofilms

Our lid margins are naturally populated with bacteria that naturally live within biofilms. All bacteria living in a natural environment live within biofilms as means of survival. As these bacterial populations within a biofilm increase above certain threshold populations, they undergo quorum-sensing gene activation and begin to produce toxins known as virulence factors. It is these virulence factors, such as lipases, cytolytic toxins, and super antigens, that directly cause the inflammation that leads to blepharitis and, in some, the long-term sequelae of dry eye disease.2

This inflammation affects the ocular surface in phases based on the anatomical relationship of the structures within the lid. Logic would presume that smaller structures of the lid would initially be affected by the accumulation of biofilm within, and larger structures-or structures more distant to the lid margin-would be affected later.

Related: How bacteria load creates a biofilm

Rynerson and Perry describe four stages of DEBS. These stages of DEBS are proposed as chronic long-term changes that occur over decades and manifest into the signs and symptoms that we know as dry eye disease.

Let’s review the order of the affected ocular structures along with the clinical manifestations that are evident at these phases.

1. Lash follicles

Not long after the entire lid margin is covered with biofilm, the lash follicle becomes the first structure to be affected by excess bacterial biofilms and associated toxins because of the follicle’s easy access and small size. When the biofilm progresses into the lash follicles, folliculitis ensues. This is a subtle clinical finding that can be easily missed on cursory anterior segment examination if not appropriately assessed.

The lash follicle manifests a volcano sign in which the skin surrounding the lash follicle is elevated with edema (Figures 2A and 2B). Many times pallor is noted as well, especially in darker-skinned patients. This is due to an “activated” toxin-producing bacterial biofilm that is present within the follicle.

As the biofilm thickens around the base of the lash, small pieces begin pull loose from the main layer due to the growing lash. The main layer of biofilm extends back across the entire lid margin, but it is nearly invisible due to its translucence and tight adherence to the lid margin.

Once the slightest amount of air gets under the biofilm, however, it becomes easily visible. This is typically when ODs are able to clinically identify blepharitis, but the process starts much sooner than visible biofilm at the base of the lashes.

It is critical to closely examine the lid margin for early volcano signs at the base of the lashes. Treatment at this stage will prevent further damage and protect the meibomian glands.

2. Meibomian glands

Years after follicular involvement, the slow “lava flow” of biofilm will extend into the meibomian gland orifices. As this occurs, the biofilm will slowly alter the fluidity of the meibum and cause it to thicken.

Obstruction at the gland orifices will initially lead to non-obvious meibomian gland dysfunction. Later, as the biofilm accumulates within the meibomian gland, it causes impaction and can lead to chalazions or hordeolums. When quorum-sensing occurs within the biofilm, clinicians will see obvious meibomian gland disease with redness of the lid margin. Unchecked, atrophy and loss of the glands will occur.

3. Glands of Krause and Wolfring

Decades later, as the biofilm continues its march, it can extend in an attenuated state along the palpebral conjunctiva, eventually reaching the glands of Krause and Wolfring. It may also reach these glands by continuously “seeding” the tear film with small bits of biofilm, known as dispersal progression.

4. Eyelid architectural changes

Lid inflammation caused by a thickened biofilm is non-selective in its slow chronic destruction, eventually affecting the medial and lateral lid tendons and sensory nerves and causing meibomian gland involution, anterior migration of the line of Marx and eyelid margin thickening. Ectropion and loss of sensation can be the long-term effect.

Challenges of biofilm removal

Identifying signs of blepharitis early is critical to promote a healthy ocular surface. According to Rynerson and Perry, these changes occur over decades. So, it is critical to identify the signs early because the downstream ramifications of excessive bacterial biofilm can eventually manifest as irreversible dry eye disease.

Decreasing the bacterial bioload and mitigating the inflammation and damage associated with excessive bacterial populations should be the goal. Lid hygiene has been utilized for decades, but lid hygiene requires good patient compliance in order to be even marginally effective.

The main challenge is that bacteria protect their decades of work by “supergluing” their biofilm to the lid margin with an adhesion molecule. Therefore, the most compliant patients will still come up short on effective biofilm removal. Antibiotics can temporarily reduce the populations of excessive biofilms on the surface of the lids, but biofilms return quickly and antibiotics can cause resistance if utilized over long periods of time.

Exfoliating lids

Some clinicians are turning to microblepharoexfoliation (MBE) as a procedure that effectively cleans the lid and provides practitioners with an opportunity to actively treat blepharitis. During the procedure, a small medical-grade microsponge is spun along the edge of the eyelid and lashes, removing years of biofilm, bacteria overload, and toxins.

This procedure has been shown to provide significant improvements in both signs and symptoms in patients with dry eye.

In an open-label study, 20 patients with meibomian gland dysfunction and dry eye symptoms underwent the MBE procedure.3 Prior to treatment, patients’ level of meibomian gland dysfunction and blepharitis using the Efron scale was graded. Tear film break-up time (TBUT) and ocular surface disease index (OSDI) scores were taken.

Four weeks later, patients’ signs and symptoms were reassessed. Signs of meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD), TBUT, and blepharitis were significantly improved. Additionally, subjective symptoms of dryness measured with OSDI were nearly cut in half.

In a separate retrospective study, more than 170 patients at multiple practices had MBE performed.4 Researchers measured TBUT, OSDI, and standardized patient evaluation of eye dryness (SPEED) questionnaire prior to treatment and again, on average, 3.8 weeks after the procedure was performed. TBUT improved by 66 percent, SPEED improved by 49 percent, and OSDI improved by 36 percent after the procedure was performed.

A poster at the 2017 Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) meeting summarized results from a study that examined MBE. Ten MGD patients who had positive InflammaDry (Quidel) test results were enrolled in the study.5 Prior to the procedure being performed, patients also underwent non-invasive TBUT and OSDI. These measurements were again taken four weeks after the procedure. Consistent with the previous studies, all measurements improved when measured four weeks after the procedure. Additionally, 100 percent of patients tested negative with InflammaDry four weeks after the procedure, indicating normal levels of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) levels on the ocular surface.

Contact lens wearers require a healthy ocular surface to optimize lens wear. In an Australian study, symptomatic contact lens wearers experienced MBE. Thirty patients were enrolled in the study; 17 were symptomatic contact lens wearers. After a single MBE procedure, 10 of the 17 were converted to asymptomatic. This represents a success rate in treating contact lens intolerance of 59 percent.6 These results can have huge implications in ODs’ everyday care of contact lens patients.

Wrapping up

DEBS provides valuable insights into the influence of biofilms on the long-term health of the ocular surface and posits that dry eye disease may not be as complex and confusing as once thought. Early identification of blepharitis is critical to preserve the health of the ocular surface, protect the meibomian glands and, in contact lens wearers, promote a comfortable wearing experience.

References:

1. Rynerson JM, Perry HD. DEBS – a unified theory for dry eye and blepharitis. Clin Ophthalmology. 2016 Dec 9;(10):2455-2467.

2. Knecht LD, O'Connor G, Mittal R, Liu XZ3, Daftarian P, Pasini P, Deo SK, Daunert S. Serotonin activates bacterial quorum sensing and enhances the virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the host. EBioMedicine. 2016 Jul;9:161-169.

3. Connor CG, Choat, C, Narayanan S, Kyser K, Rosenberg B, Mulder D. Clinical effectiveness of lid debridement with blephex treatment. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015 June;56(9):440. Available at: https://iovs.arvojournals.org/article.aspx?articleid=2334385&resultClick=1. Accessed 9/11/18.

4. Epitropoulous A, et al. Blephex – A Retrospective Analysis of Data Pre and Post Treatment. Available at: https://simovision.com/assets/Uploads/Study-A-retrospective-Analysis-of-Data-Pre-and-Post-Treatment-Dr.-A.-Epitropoulos-EN.pdf. Accessed 9/14/18.

5. Connor CG, Narayanan S, Miller W. Reduction in inflammatory marker matrix metalloproteinase-9 following lid debridement with BlephEx. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017 June;58(9):448. Available at: https://iovs.arvojournals.org/article.aspx?articleid=2638666&resultClick=1. Accessed 9/11/18.

6 Siddireddy JS, Tan-Showyin J, Vijay AK, Willcox M. A Comfortable Eye Needs Fats. Thesis competition at the University of South Wales, Sydney, 2015.