How to diagnose Zika virus in your practice

The Zika virus has been rapidly on the move in Central and South America. With global travel on the rise and new cases being confirmed daily in Canada, Europe and the United States, chances are this may be a condition you encounter in your practice.

The Zika virus has been rapidly on the move in Central and South America. With global travel on the rise and new cases being confirmed daily in Canada, Europe and the United States, chances are this may be a condition you encounter in your practice.

What is Zika virus?

The Zika virus (ZIKV) is a RNA virus first identified in 1947 by researchers in Uganda studying yellow fever and was named after the forest in which it was discovered.1-3 The first recorded human infection was in 1952, and the virus has caused sporadic human infections in areas of Africa and Southeast Asia over the last 60 years.2 In 2007, a large outbreak occurred in the Pacific Islands and was the first evidence of ZIKV outside of Africa.4 Subsequent years saw the virus spread quickly to surrounding areas before arriving in South America, particularly Brazil, in 2015 where it has been suspected to correlate with an increase in the birth defect microcephaly.5

Recent news:

Transmission

The majority of cases of ZIKV are acquired through the bite of a specific species of infected mosquito, AedesAegypti.2,4,6 However, there are documented cases of mother-to-newborn transmission during labor as well as viral spread via blood transfusions and sexual contact.3,7,8 More recently, the American Red Cross requests that potential donors who have traveled to areas where ZIKV infection is active to wait 28 days before donating blood.9

Sexual transmission of ZIKV is possible, although only a few cases have been documented. In two cases, the infected men transmitted the virus to their female partners. The third case documents replication-competent ZIKV isolated from semen at least two weeks after illness onset with no detectable levels of the virus remaining in the bloodstream. In all three cases, the men developed symptoms of ZIKV.10

It is not known if asymptomatic individuals can sexually transmit the virus, and there have been no reported cases of infected female transmission to partners.10 At this time, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommends that men who reside in or have traveled to an area of active ZIKV transmission who are concerned about sexual transmission of the virus might consider abstaining from sexual activity or using latex condoms consistently and correctly during sex.11

The implications of local non-vector transmission could pose a serious public health concern, especially for women of childbearing age given evidence of perinatal transmission and congenital infection.12,13

The Aedes mosquito in question is no stranger to viral transmission-this particular mosquito species is known to spread other illnesses including dengue and chikungunya viruses.2,4 Like other flying pests of its kind, the Aedes mosquito lays eggs in and/or near standing bodies of water such as pet bowls, flower pots, and vases and can breed in and outside the home.7,14 Furthermore, this aggressive species feeds most actively during the day and has a preference for people (as opposed to livestock or other animals). The mosquito acquires the virus after biting an infected individual and may then spread the virus to other people.

Signs and symptoms

Following the bite of an infected mosquito, symptoms may appear after an incubation period of a few days to a week. According to the Center for Disease Control (CDC), only one in five people bitten by an infected mosquito go on to develop symptoms of the illness.14 The most common symptoms include fever, maculopapular rash, joint pain, and conjunctivitis. Additional symptoms include headache (retro-orbital pain), fatigue, malaise, and muscle pain over a few days because the viral incubation time is approximately two to 14 days.3-5

According to the CDC, illness associated with ZKV virus is typically mild-healthy individuals will develop ZIKV antibodies in three to four days and fully recover. Severe cases requiring hospitalization are uncommon, and death associated with ZIKV is rare.14

There are reports of other neurological and autoimmune complications, including Guillain-Barré Syndrome, which have also risen in areas associated with ZIKV outbreaks.15

The health risk and long-term implications are more concerning for pregnant women because ZIKV has been shown to pass through amniotic fluid to the developing fetus and has been associated with congenital anomalies.5,13,16 In a statement released by the CDC, experts agree that a causal relationship between ZIKV infection during pregnancy and microcephaly is strongly suspected, though not yet scientifically proven.14 Presence of the virus was recently found in the brain tissue of a microcephalic fetus of a woman who had symptoms of the virus during her pregnancy while living in Brazil.13

Formulary Watch:

Microcephaly is a congenital condition that results in an abnormally small skull with the potential for incomplete brain development. The accompanying complications surrounding this neurological disorder may result in severe developmental delays and even death. In Brazil alone, there has been a twentyfold increase in cases of microcephaly in 2015 in comparison to the rate observed in previous years.5

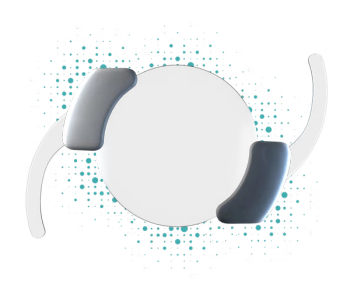

Recent studies have also demonstrated ocular complications in infants with presumed congenital ZIKV infection, including but not limited to macular mottling, chorioretinal atrophy, and optic nerve abnormalities (pallor, hypoplasia, and increased cup-to-disc ratio).17,18 The complications of this illness and these vision-threatening conditions could have significant impact on countless families throughout the continent.

Diagnosis and treatment

For healthcare practitioners, the differential diagnosis based on clinical symptoms is unreliable due to the clinical similarity of ZIKV and other infections such as dengue, yellow fever, and West Nile, all carried by the same mosquito vector.6 At present time there is no commercially available diagnostic tests for ZIKV, and testing requires the CDC Arbovirus Diagnostic Laboratory. The diagnostic test may be performed during the first week after onset of symptoms by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) on serum.6,19 But ZIKV can be misidentified as dengue as a result of antibody cross-reactivity if testing is delayed more than a week after initial exposure.

Recent:

Currently there is no vaccination or cure against ZIKV, and palliative care of symptoms is recommended. Fluid replenishment and rest are the primary treatments for the systemic symptoms. Aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs including ibuprofen and naproxen are not recommended in case of co-infection with dengue due to an increased risk of bleeding.7,14

The eyes are red, now what?

Adenovirus conjunctivitis is highly symptomatic, causing discomfort, redness, photophobia, and tearing in patients. ZIKV conjunctivitis is no different. That being said, even those with an active ZIKV illness may be asymptomatic or present with minimal complaints.

Despite the symptoms, a good case history is essential in making the diagnosis.

If you encounter a patient with an acute conjunctivitis that cannot be attributed to any other cause, further questioning is crucial. Lack of recent travel to an infected country does not rule out ZIKV as potential cause. Transmission may occur through blood transfusion or from a spouse or household member with recent travel to an active illness area.3, 8,10

Related:

Depending on when this patient presents to you in the incubation period, they may or may not have any node involvement, but a quick check of the preauricular nodes can help confirm a viral diagnosis. On slit lamp examination, does the patient have any follicles, chemosis, or sub-epithelial infiltrates? If clinical findings lend support to the viral diagnosis, although not specific to ZIKV, the use of the Rapid Pathogen Screening (RPS) AdenoPlus Detector may be warranted to rule out other viral causes. As ZIKV is a self-limiting condition, artificial tears and cold compresses may be the most appropriate form of treatment to relieve discomfort. If the patient presents early in the course of the infection, ophthalmic Betadine 5% (povidone iodine, Alcon) may significantly improve symptoms. Although there is documentation of infection via bodily fluids,3 to date there have been no reports of ZIKV transmission through conjunctivitis. The patient should still be counseled on hygiene to prevent further viral transmission.

A complaint of retro-orbital pain, although non-specific to ZIKV, warrants further evaluation. However as often is the case, the patient’s history should provide better context to the reported symptoms, especially onset and modifying or associated factors. Ophthalmic examination of the extraocular muscles, and evaluation of the optic nerve appearance and visual fields can help rule out differential diagnosis of neurologic conditions or a lesion in the brain. Acetaminophen may be recommended for short-term pain management.

If additional systemic symptoms of ZIKV are noted, the patient should follow up with his primary-care provider as soon as possible.

Prevention

Anyone can become infected with ZIKV if the circumstances are right. As a ZIKV vaccine has not yet been established, the mainstay of prevention is elimination of the vector, the mosquito. Nationwide campaigns have commenced in areas of active transmission in attempts to reduce the spread.

Travelers to these countries should follow recommendations from the CDC to reduce exposure to mosquitos, which include but are not limited to the following:

• Wear long-sleeved shirts and long pants

• Use insect repellant to reduce the number of mosquito bites (DEET is recommended but not required)

• Use door and window screens to keep mosquitos outside

• Frequently remove/empty standing bodies of water

If you have recently returned from an active area, the CDC recommends the above guidelines be followed for seven to 10 days to prevent mosquito bites even if asymptomatic.

What’s next?

As of February 2016, ZIKV illness is a nationally notifiable condition in the United States, and healthcare providers are encouraged to report suspect ZIKV cases to their state or local health departments. Researchers are currently investigating other transmission routes as well as the association among the virus, Guillain-Barré, and microcephaly.

Given the worldwide spread of other viral illnesses associated with globalization and climate change, as well as the unknown long-term impact of the virus, chances are we will continue to see ZIKV dominate news headlines for months to come. For an up to date list of countries with active transmission, the see the WHO website,

References

1. Dick GW, Kitchen SF, Haddow AJ. Zika virus. I. Isolations and serological specificity. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1952;46: 509–20.

2. WHO. Zika Virus Outbreaks in the Americas and Malaria situation 2015. Weekly Epidemiological Record. 2015 Nov 6. Available at: http://www.who.int/wer/2015/wer9045.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 2/3/16.

3. Musso D, Roche C, Robin E, Nhan T, Teisser A, Cao-Lormeau VM. Potential sexual transmission of Zika virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015 Feb;21(2):359-61.

4. Oehler E, Watrin L, Larre P, Leparc-Goffart I, Lastère S, Valour F, Baudouin L, Mallet HP, Musso D, Ghawche F. Zika virus infection complicated by Guillain-Barré syndrome-case report, French Polynesia, December 2013. Euro Surveill. 2014 Mar 6;19(9).

5. PAHO. Neurological syndrome, congenital malformations, and Zika virus infection. Implications for public health in the Americas. Epidemiological Alert. 2015 Dec 1. Available at: http://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_view&Itemid=270&gid=32405&lang=en. Accessed 2/3/16.

6. Lanciotti RS, Kosoy OL, Laven JJ, Velez JO, Lambert AJ, Johnson AJ, et al. Genetic and serologic properties of Zika virus associated with an epidemic, Yap State, Micronesia, 2007. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008 Aug;14(8):1232-9.

7. WHO. Zika virus. 2016 Jan. http://www.who.int/topics/zika/en/. Accessed 2/3/16.

8. Foy BD, Kobylinski KC, Chilson Foy JL, Blitvich BJ, Travassos da Rosa A, Haddow AD, et al. Probable non–vector-borne transmission of Zika virus, Colorado, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011 May;17(5):880-2.

9. American Red Cross. Red Cross Statement on the Zika Virus. 2016 Feb 3. Available at: http://www.redcross.org/news/press-release/Red-Cross-to-Implement-Blood-Donor-Self-Deferral-Over-Zika-Concerns. Accessed 2/4/16.

10. Oster AM, Brooks JT, Stryker JE, et al. Interim Guidelines for Prevention of Sexual Transmission of Zika Virus-United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:120–121. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6505e1

11. Petersen EE, Staples JE, Meaney-Delman, D, et al. Interim Guidelines for Pregnant Women During a Zika Virus Outbreak - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:30–33. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6502e1.

12. Staples JE, Dziuban EJ, Fischer M, et al. Interim Guidelines for the Evaluation and Testing of Infants with Possible Congenital Zika Virus Infection - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:63–67. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6503e3.

13. Rubin EJ, Greene MF, Baden LR. Zika Virus and Microcephaly. N Engl J Med. 2016 Feb 10. [Epub ahead of print]

14. CDC. Zika Virus. 2016. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/zika/index.html. Accessed 2/3/16.

15. WHO. WHO Director-General summarizes the outcome of the Emergency Committee regarding clusters of microcephaly and Guillain-Barré syndrome. 2016 Feb 1. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2016/emergency-committee-zika-microcephaly/en/. Accessed 2/4/16.

16. Besnard M, Lastère S, Teissier A, Cao-Lormeau VM, Musso D. Evidence of perinatal transmission of Zika virus, French Polynesia, December 2013 and February 2014. EuroSurveill. 2014 Apr 3;19(13).

17. Ventura C, Maia M, Ventura BV, Linden VV, Araújo EB, et al. Ophthalmological findings in infants with microcephaly and presumable intra-uterus Zika virus infection. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2016 Feb;79(1):1-3.

18. de Paula Freitas B, de Oliveira Dias JR, Prazeres J, et al. Ocular Findings in Infants With Microcephaly Associated With Presumed Zika Virus Congenital Infection in Salvador, Brazil. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016 Feb 9. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.0267. Epub ahead of print.

19. Buathong R, Hermann L, Thaisomboonsuk B, et al. Detection of Zika Virus Infection in Thailand, 2012–2014. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015 Aug;93(2):380-3.

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.