Know the benefits of adopting neuroimaging

Neuroimaging can help ODs better treat patients with possible tumor, vascular disorder, or demyelinating disease. CT scans are used for bone fractures and vascular disorders as well as orbital and pituitary tumors. MRIs are best gliomas and menigiomas and screening for vascular disorders. Communicate to radiology patient history and what you are trying to rule out when ordering tests.

Few subjects can intimidate even a seasoned optometrist like neuroimaging. When to order? What type of scan to order? How to utilize the results?

Knowing the answers to these fundamental questions and having a basic understanding of imaging will aid the optometrist in knowing how to best manage the patient and when and where to refer the patient if needed.

Types of imaging

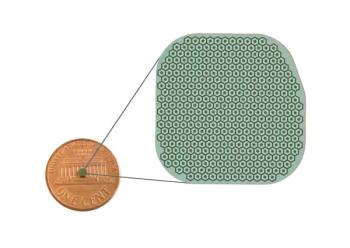

Computerized tomography (CT) scan. A conventional CT takes multiple X-rays, often moving the patient between scans, and these images are pieced together with computer software to produce a 3-dimensional image. Most CT devices utilize a spiral or helical approach for increased resolution and less radiation.1

This technology is best for bone fractures from trauma and, increasingly, vascular disorders with CT angiography.2 CT scanners are often used to locate larger orbital and pituitary tumors, although a magnetic resonance image (MRI) is the instrument of choice for small tumors such as meningiomas.3,4

Related:

A CT scan is typically done with intravenous iodine contrast dye, provided the patient has no known sensitivity to iodine, to enhance the images. Advantages of the CT include being readily available and relatively inexpensive. A CT may also be used if a patient has a contraindication to an MRI, such as a pacemaker or other known or suspected metal in the body.4

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). A magnetic field causes hydrogen protons in water and fat to spin and release photon energy. The MRI is the instrument of choice for soft tissue concerns such as plaques associated with multiple sclerosis.5 MRIs are superior to CT scans for subtle tumors such as gliomas and menigiomas.4,6 MRIs may also be used as a screening device for vascular disorders, although a magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) or CT angiogram is typically the definitive test.2

With an MRI, a contrast dye such as gadolinium is often administered intravenously to aid the images seen. Before ordering imaging with contrast, it is prudent to evaluate the patient’s kidney function by ordering a blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine level test.

When ordering an MRI for optic neuritis and suspected multiple sclerosis, fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) is added to suppress the return from cerebrospinal fluid that might mask demyelinating plaques.

What to order

Before ordering a test, communicate with your radiologist and staff. They can help you determine the best test for what potential condition or diagnose you’re examining.

As an example, Tommy Hinton, MD, a radiologist in northwestern Arkansas, says, “The more clinical information we as radiologists can get from the referring doctor, the better off we are. Unfortunately, many of the imaging requests we receive have very little clinical history. If you can state a brief patient history and what you are trying to rule out, it would help us immensely to tailor our protocol accordingly.”

While interdisciplinary communication is always key, collaborating with radiology has the additional benefit of taking some of the burden off the referring optometrist to order the precisely correct scan, contrast dye, etc. Instead, a good patient history and a clear indication of what you’re looking for or wishing to rule out will help ensure the patient receives the proper radiological care.

Related:

Typically, trauma such as a blow-out orbital fracture or a possible space-occupying lesion will require a CT scan. A potential example of the latter would be a patient with bitemporal visual field loss and a suspected pituitary adenoma or a patient with suspected idiopathic intracranial hypertension in which an actual tumor must be excluded from possible diagnoses. Other instances may include recent onset proptosis or an atypical ischemic optic neuropathy in which a lesion must be ruled out.

A scan of the brain and orbits to discover demyelinating disease is the most common use of an MRI for the optometrist, but the MRI may also be used if a subtle tumor is theorized. A suspected aneurysm, possibly associated with a worsening, painful third cranial nerve palsy or a blown pupil, may require a conventional catheter angiogram, an MRA or, increasingly, a spiral CT angiogram.2,7

Case 1

A 42-year-old Native American male presented to our clinic with an increasing headache over the last week. He had difficulty pinpointing the exact location of the pain but noticed a sparkling blue light off to his left side for the last four days. His history was significant for uncontrolled diabetes and hypertension despite being prescribed insulin, lisinopril, and hydrochlorothiazide.

Visual acuity in each eye was 20/20, and extraocular muscles (EOMs), pupils and slit lamp findings were normal. Reduced arcuate fields were noted on his left side. Dilated fundus exam revealed mild non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy. An automated visual field was run (Figures 1 and 2).

Due to the congruent nature of the visual field defect, the patient’s systemic history, and the recent onset of worsening symptoms, we elected to order an MRI with and without contrast to rule out a space-occupying lesion or intracranial bleed. We first ordered BUN/creatinine blood tests, which were normal, then communicated the patient’s history and visual field findings with the consulting radiologist.

Related:

The MRI (Figure 3) showed no mass lesion, no evidence of acute hemorrhage, nor any acute intracranial abnormality or abnormal areas of enhancement. Although negative, the MRI was useful as a diagnosis of exclusion. We made a diagnosis of intractable migraine secondary to uncontrolled cardiovascular disease and worked with patient’s primary-care provider for blood sugar, blood pressure, and pain management.

Case 2

A 35-year-old, obese white female reported to our clinic with complaints of decreased vision in her left eye with mild pain behind and around the eye for the last two days. The patient reported no health problems or current medications but did state that she had been fairly fatigued recently.

Best corrected acuities were 20/20 OD and 20/30 OS. EOMs, pupils, confrontational fields, and slit lamp examination were normal. Dilated fundus exam revealed a normal optic disc in the right eye and a mildly swollen optic disc with indistinct margins in the left eye.

While the patient’s demographics and body mass index (BMI) made idiopathic intracranial hypertension a consideration, the unilateral nature and the patient’s history pointed toward optic neuritis. A space-occupying lesion had to be ruled out as well. After confirming the patient’s healthy kidneys via a blood test, an MRI with FLAIR of the brain and orbits was ordered. We forwarded to radiology the patient’s history and clinical findings along with a message that the purpose of our MRI order was to “rule out demyelinating disease or tumor.”

The MRIs (Figures 4 and 5) showed multiple lesions, and the report stated that no mass was seen but “multiple nonspecific, hyperintense foci are seen in the periventricular white matter and subcortical white matter as well as enhancement of the optic nerve…the constellation of findings are most compatible with multiple sclerosis.”

Related:

The diagnosis of multiple sclerosis was made, and the patient was promptly referred to a neurologist for care.

Conclusion

While usually not a daily part of optometric life, neuroimaging does not need to be an intimidating subject. Worsening neurological symptoms from a possible tumor, vascular disorder, or demyelinating disease all warrant further investigation with a CT and/or MRI. Prompt referral as well as proper communication with the radiologist can ensure these patients receive the correct diagnosis and care.

References

1. Goldman LW. Principles of CT: multislice CT. J Nucl Med Technol. 2008 Jun;36(2):57-68; quiz 75-6.

2. Brown RD Jr, Broderick JP. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: epidemiology, natural history, management options, and familial screening. Lancet Neurol. 2014 Apr;13(4):393-404.

3. Lee HJ, Jilani M, Frohman L, Baker S. CT of orbital trauma. Emerg Radiol. 2004 Feb;10(4):168-72.

4. Saloner D, Uzelac A, Hetts S, Martin A, Dillon W. Modern meningioma imaging techniques. J Neurooncol. 2010 Sept;99(3):333-340.

5. Ge Y. Multiple sclerosis: the role of MR imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006 Jun-Jul;27(6):1165-76.

6. Greenfield G, Arrington JA, Kudryk BT. MRI of soft tissue tumors. Skeletal Radiol. 1993;22(2):77-84.

7. Burrill J, Dabbagh Z, Gollub F, Hamady M. Multidetector computed tomographic angiography of the cardiovascular system. Postgrad Med J. 2007 Nov;83(985):698-704.

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.