Making the most of advanced technology

Embracing new technology is good for patients and provides protection against malpractice claims.

There is always a balance when it comes to acquiring new technology for an optometric office. Practitioners have to consider the clinical value of new technology, its cost and reimbursement level (if any), as well as space and time constraints in the office. Although that is already a lot to weigh, I would suggest that most clinicians do not pay enough attention to their medicolegal risks in making these decisions. There is a misconception that newer technology might introduce medicolegal risk and that doing what you have always done is the safe path. In fact, the opposite may be true.

A duty of care

As physicians, we have a duty to provide our patients with high-quality care. There is a strong legal precedent for this concept in eye care. In a 1974 court case, Helling v Carey, the Washington State Supreme Court ruled in favor of a woman who developed severe vision loss due to glaucoma. At that time, IOP was not typically measured in patients younger than 40 years.1 Over the course of a decade, her physicians had never checked her IOP, instead attributing her visual complaints to complications of rigid contact lens wear. The court recognized that even if a given practice (eg, IOP measurement in younger patients) is not universally followed, a duty of care can still exist if the failure to perform a simple test leads to serious harm.

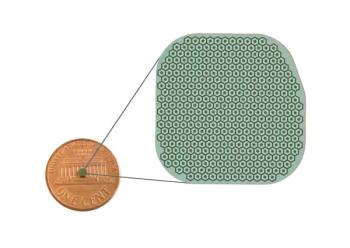

This case is the reason we now test IOP in patients of all ages, but its broader implications are sometimes ignored. For example, we have technology (corneal topography) that can detect changes in the cornea indicative of keratoconus, a sight-threatening disease. As corneal topography has become more affordable and accessible, with built-in algorithms that make it easier to interpret, the argument for integrating it into routine eye examinations has become stronger. In my practice, I use the multifunctional Topcon KR-1W, which combines aberrometry, topography, keratometry, pupillometry, and autorefraction in a single unit. All the data are captured during the pretest process for every patient, but the topography is only uploaded for me to review and interpret when there is some clue to keratoconus, such as high cylinder or a significant power differential between the 2 eyes. If I cannot refract the patient’s vision to 20/20 or if I find something else of concern during my examination, I can acquire the corneal topography report with just a few clicks. This capability helps me to uncover diseases earlier than I would otherwise (Figure 1), which means I can intervene earlier.

For example, I can detect keratoconus earlier and monitor for progression, including seeing young patients with suspicious findings in a few months instead of a full year to repeat the topography. Once there is any sign of progression, I can refer the patient for corneal cross-linking (iLink; Glaukos) to halt the progression and stabilize the cornea before vision is permanently lost. I find that having a single, integrated device makes me more efficient, and it ensures we are screening all patients effectively. Some practices rely on a standalone topographer and order testing when indicated, but using the topographer more broadly might help to uncover more issues. At minimum, optometrists need to refer for topography when there are red flags. Ignoring those red flags because the technology to investigate further is not available in the office is not acceptable.

Similarly, we have a duty to carefully evaluate any patient with cataracts to determine whether they also have ocular hypertension or any signs of glaucomatous damage. If so, they should be offered minimally invasive glaucoma surgery at the time of cataract surgery because it is a one-time opportunity to address IOP with a combination procedure.

Retinal optical coherence tomography (OCT) and a dark adaptometer are other indispensable tools in my practice for earlier diagnosis of retinal disease. Retinal OCT devices such as Optomap (Optos) or Spectralis OCT (Heidelberg Engineering) are now valued by most optometry clinics for their ability to facilitate a quick assessment of the optic nerve, macula, retinal vasculature, and more. Dark adaptation testing, performed with a wearable device such as Prime (Heru) or AdaptDx Pro (LumiThera) (Figure 2), is an easy test that measures impaired rod function, an early sign of age-related macular degeneration (AMD). By detecting AMD before there are clinical signs, we can put patients on the right path to preventing progression of AMD.

In my view, optometrists can and should embrace advancements in technology such as these that allow us to detect, diagnose, and intervene early, when the impact of intervention is the greatest. That does not mean it is malpractice not to have these specific technologies. No court would expect every physician to obtain every possible diagnostic device. However, I believe we all need to think about ways to integrate newer technologies into our clinical protocols so that we are providing the highest level of care for our patients.

Take the time to investigate

A key element in Helling v Carey was that the physicians in this case had failed to explore the reasons for their relatively young patient’s vision problems. Any time a patient has reduced vision, we need to determine whether the cornea, lens, optic nerve, or retina is the source of the problem. If you cannot solve the puzzle yourself or do not want to invest in the resources to do so, a referral should be made to someone else who has more advanced diagnostic technology. Skipping this diagnostic step may negatively affect patient treatment outcomes as well as result in practice litigation.

A busy schedule is not a reasonable excuse. “I didn’t have time” is not going to be a very satisfactory answer to a patient who has suffered vision loss—let alone at a deposition for a malpractice case. If you do not have time to effectively screen for a wide array of ocular conditions and diseases, consider how to restructure your schedule or use technology or staffing changes to help you become more effective in the same amount of time. For instance, including topography in all eye examinations may only add 30 seconds to a pretest. For most offices, this may be more efficient than having to schedule separate topography when there is some concern during the examination.

For me, the answer to the perennial time crunch is to have staff collecting all the testing data for me. I have established clear guidance for abnormal values that should be flagged or should generate additional testing. I use advanced imaging not only for diagnosis but also for effective communication with patients and the other physicians to whom I refer. I have invested time in drafting referral templates so that my busy schedule does not become an unnecessary barrier to needed care.

We all want to avoid the emotional and financial costs of a medical malpractice case. Embracing technology and practicing to the highest level of care is a great way to protect yourself while providing optimal patient care.

Reference:

Helling v Carey, 83 Wn2d 514, 519 P2d 981 (Wash 1974). Accessed April 18, 2025. https://law.justia.com/cases/washington/supreme-court/1974/42775-1.html

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.