Neural adaptation in refractive care

This neural time warp is seen throughout the optometric examination.

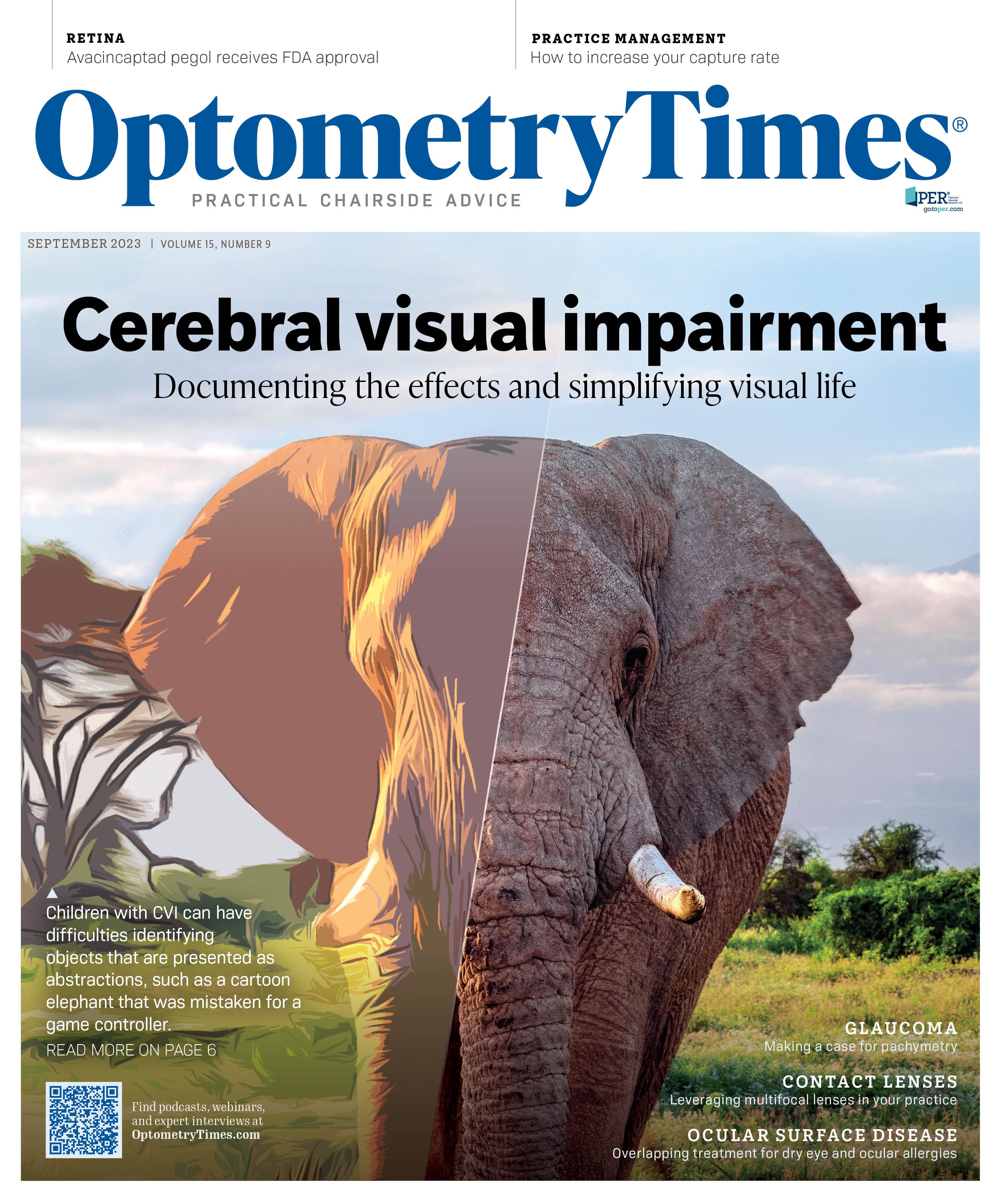

The concept of neural adaptation is more commonly a phenomenon of decaying neuronal activities in response to repeated or prolonged stimulation. (Adobe Stock / Generative ART)

One of the positives of technology—and especially social media—is the ability to find short clips or unique content that was not accessible unless you specifically sought it out. For example, the TikTok algorithm finds topics and videos that it intuitively knows you will enjoy. The Tiny Desk Concert series from PBS perfectly represents the “who knew?” And “where have you been my whole life?”One that stands out is Cypress Hill. Yes, that Cypress Hill. “Who you trying to get crazy with, ese? Don’t you know I’m loco?”

For those of you who are still reading this article and have not questioned whether you inadvertently picked up Rolling Stone, you only need to hum that 1993 classic from the Black Sunday album: “Insane in the membrane, insane in the brain, crazy insane got no brain.” The irony of that statement is such that as clinicians we are almost always thinking this exact sentiment. As optometrists we rely more on our patients’ cognitive abilities—or neural adaptation—as an answer to most of our patients’ visual complications.

The concept of neural adaptation is more commonly a phenomenon of decaying neuronal activities in response to repeated or prolonged stimulation. Rather, give it some time and you will get acclimated to it. Neural adaptation is observed all the way along neuronal pathways from the sensory periphery to the motor output, and adaptation usually gets stronger at higher levels.

In fact, nonadapting neurons—or neurons that increase their sensitivity—are rare exceptions: insane in the brain. At the beginning of my optometric career, the concept of neural adaptation was a construct used to help patients understand why they didn’t see as well with their new multifocal lenses. As far back as the early 2000s, it was not common to think of vision as made up of an optical system, which is the cornea, the crystalline lens, and the media and a sensory system that begins at the retinal photoreceptors and goes all the way back to the occipital cortex.

We can all remember learning about the neural processing from the retina, as the optic nerve relays visual information to Brodmann area 17, 18, and 19 before it makes it to the occipital lobe. Jack Holladay, MD, MSEE, FACS, pioneered the research and was a thought leader regarding this new concept. Holladay likened the occipital cortex to a sophisticated, image-enhancing computer. The occipital lobe works to make visual corrections and fills in areas the brain perceives to be blurred; this is the short phase of neural adaptation and it can occur within seconds to minutes. However, the long phase of adaptation may take months.

The practicality of this neural time warp is encountered in almost all aspects of the optometric examination: when patients ask why they are seeing veins and arteries as we do a binocular indirect ophthalmoscope and how patients with a congenital cataract are astonished to learn there is an opacity in their lens. You want to wear monovision contacts, then adapt. Progressive lens? Floaters? What is your go-to when a patient complains about the “gnats” or “cobwebs”? They mustn’t be crazy insane because they must have a brain. Yes, I will keep referencing Cypress Hill—or maybe you will neural adapt to the continued reference. Moreover, when we are managing our refractive surgery patients, the concept of adaptation must be the first and last thing that you speak about.

When it comes to refractive surgery, everything about neural processing for vision has been disrupted. I used to quip that the absolute best patient I could refer for surgery was the uncorrected patient who is content with seeing less than 20/20. Think about that patient you fit for their first contact lens or glasses. The awareness that they have been lacking, the clarity is astonishing. Now imagine doing refractive surgery on that patient. Anything we do to improve the vision is golden. Whether it is lens-based or corneal refractive surgery, the cortex must adapt to the altered high- and low-order aberrations, the refracting surface, and most importantly the difference from the vision they “thought” was great before surgery.

While most patients adapt quickly, some take months—and even years—to adapt or accept the fact that they will not adapt. Since we have been swirling in this silver tsunami for a while with no end in sight, the multifocal IOLs are only going to become more common place. The dysphotopsia first encountered by patients will need to neural adapt and just as important is our ability to guide our patients through this period. Take the time to let patients know it will subside. Another important reminder is the benefits the patient is experiencing away from their dysphotopsia. Since we are talking about the brain, don’t forget the psychological benefit of reminding the patients how well they do in daylight.

Patients may feel that they are insane in the brain primarily after any new refractive change. We need to reinforce the fact that the cortex is a plastic tissue and although it may take time, they will gain acceptance to the new way of seeing. Yet if they don’t, they may just question whether they are crazy.