Anterior segment imaging may have saved a life

With the advent of advanced anterior segment imaging, we as optometrists are tasked with the responsibility of going beyond knowing the basics of the eye’s anatomy.

There is a misunderstanding among patients that when they are examined in an optometrist’s office, their entire eye is being examined. In reality, the optometrist is examining every part of the eye except the ciliary body. But with the advent of advanced

Imaging the anterior segment is helpful in the differential diagnosis of open-angle glaucoma from glaucomas with abnormal angles, but it will also enable us to make diagnoses that aren’t necessarily common, such as tumors. Although it is rare that a patient presents with a mass lesion in the anterior segment, it is possible, and anterior segment imaging devices are the only imaging modalities available through which optometrists can view the ciliary body. The following case is an example of how my colleague, Sanjeev Nath, MD, and I made a discovery during imaging of the anterior segment that may have saved a patient’s life.

Case presentation

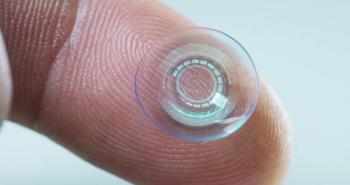

Figure 1A 71-year-old woman was a patient at the Eye Institute and Laser Center in New York for approximately 5 years, where she received routine eye care. She underwent an uneventful cataract extraction and an implantation of a posterior chamber intraocular lens (IOL). Her vision had always been good, and she had never had any significant problems. Prior to her cataract surgery, she had an ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) (Aviso, Quantel) of the anterior segment and ultra-widefield retinal imaging (Optos). Both sets of images were interpreted as normal.

The patient presented in the summer of 2013 with a new complaint. She explained that, about 2 weeks prior, her daughter recognized that when the patient looked to the left, her right eye was red on its right side. The patient’s visual acuity was 20/20 and her intraocular pressures (IOPs) were normal in each eye. However, we did recognize that her eye was hyperemic temporal to the limbus in the right eye. When we examined the eye, we noticed that the superficial vessels of the conjunctiva didn’t blanch with the application of neosynephrine. We performed ultra-widefield retinal imaging, which we do routinely, and recognized an elevated lesion in

Figure 2the far temporal periphery in the right eye at 9 o’clock (Figure 1). It had the appearance of retinoschisis (which is present in about 1% of all patients) but appeared solid.1 We then performed UBM, which confirmed the presence of a solid lesion (Figure 2)

Fortunately, David Abramson, MD, chief of the ophthalmic oncology service at Memorial Sloan Kettering in New York, has a private practice on the same street as our office. Knowing that the patient had a serious problem, I was truthful with her and told her that I thought she had a tumor in her right eye, and that I wanted her to be seen by one of the world’s experts. I physically walked her over to the office to ensure that she scheduled an appointment as soon as possible. The patient was seen within a matter of days, and Dr. Abramson and colleagues confirmed the presence of a ciliary body malignant melanoma, which appeared to be extending to the anterior choroid.

The patient was treated with a radioactive plaque, which was placed on the surface of the globe corresponding to the location of the tumor for a period of time. The plaque was made of iodine that emits radiation, killing the tumor cells. The plaque was then removed, and over the next several months, the patient’s tumor shrunk significantly. Ciliary body malignant melanomas are usually primary and can spread to other parts of the body, so the patient had a positron emission tomography (PET) full body scan to confirm there were no other tumors in her body. Once the primary tumor is destroyed, there is little probability of it spreading to any other part of the body.

When a red eye is something more

The vast majority of red eyes are easy to diagnose and easy to treat, but about 1% fall into the category of the "not-so-simple red eye.”2 The differential diagnosis of lesions in the ciliary body include cystic lesions of various sizes, and in our experience, appear to be present in about a quarter of all patients who undergo UBM. In contrast, a malignant melanoma is present in about 5 to 7 cases per year per million in the Caucasian population.3-5

In this particular case, a red eye was the patient’s only complaint. Pain or vision loss was not reported. It would have been possible for us to diagnose a “simple red eye,” and treat the patient with an antibiotic and steroid combination. If we had taken that approach, the steroid would more than likely have reduced the redness, and the anti-inflammatory properties would have temporarily shrunk the size of tumor. This would have been a danger to the patient because the symptoms would have appeared to fade and the melanoma would have been masked for a longer period of time, increasing the chances that it would spread to a different part of the body, such as the liver, and become fatal.

Optometrists see patients with red eyes all the time, but they virtually never see the ciliary body. The anatomy of the eye is such that the ciliary body is hidden behind the iris. Because the iris is not transparent, we can’t visualize the ciliary body behind it using only light instruments, such as slit lamps, because light images transmit light only through clear media. Other technologies, such as UBM, utilize sound waves that pass through opaque normal structures, such as the iris, and also allow us to see through opaque media like dense cataracts.

UBM used in conjunction with a B-scan ultrasound is a great tactical combination because the UBM provides high resolution of the anterior segment while the B-scan provides deep penetration to the posterior segment and even behind the globe and into the orbit. Both images revealed a solid mass in this case. Surprisingly, a third image from the ultra wide-field retinal imaging also confirmed the mass, but ultra-widefield imaging does not usually show lesions of the ciliary body, meaning that the tumor most likely had grown from the ciliary body into the contiguous anterior choroid.

The patient was fortunate, first, that we had the necessary technology to view the anterior segment of her eye and visualize the melanoma, and second, that we were able to directly connect her to a renowned ophthalmic oncologist. This case is a leading example of why optometrists should consider obtaining anterior segment imaging in patients who present with a red eye without an obvious diagnosis. UBM can differentiate a common ciliary body cyst from a solid mass and perhaps save a life.ODT

References

1. Straatsma BR. Clinical features of degenerative retinoschisis. Aust J Ophthalmol. 1980 Aug;8(3):201-6.

2. Cronau H, Kankanala RR, Mauger T. Diagnosis and management of red eye in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2010 Jan;81(2):137-44.

3. Seregard S, Daunius C, Kock E, Popovic V. Two cases of primary bilateral malignant melanoma of the choroid. Br J Ophthalmol. 1988 Apr;72(4):244-5.

4. Damato B. Atlas of intraocular tumours. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000 Jul;84(7):805B-805.

5. Mellen PL, Morton SJ, Shields CL. American joint committee on cancer staging of uveal melanoma. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2013 May;6(2):116-8.

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.