Improve your detection rate of retinal neovascularization

If a complete examination is not possible in diabetic patients, pay close attention to the inferior retina.

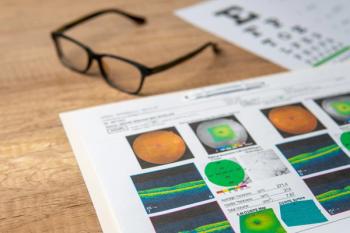

A thorough dilated fundus evaluation both at the slit lamp and binocular indirect should be a part of any comprehensive eye examination. This evaluation takes on even more significance in patients at risk for retinal-related vision loss. As one of the most common potentially blinding retinal diseases, patients with diabetes and diabetic retinopathy require close attention in their retinal examination. However, a number of factors may reduce ODs’ rate of detection for significant findings such as retinal neovascularization (Figure 1) during clinical examination. These include media opacities, patient pupil size, patient cooperation, and retinal landscape changes by the disease or past treatments such as laser (Figure 2).

Clinical signs

A systematic fundus examination allows ODs to organize their abilities to detect the most. First, examine the vitreous by looking at it instead of through it. Then, examination of the optic nerve, macula, and vascular arcades are followed by mid- and peripheral retina.

During examination of the peripheral retina, dividing the landscape every 2 clock hours or 4 quadrants keeps in line with this systematic or disciplined assessment. A 100 percent yield in detection of abnormalities is not achieved every time.

I particularly pay close attention to the inferior retina when suspecting retinal neovascularization (NV). In addition to other tell-tale signs, I am looking for presence of any degree of hemorrhage on the retinal surface (also known as preretinal hemorrhage). Leakage of blood from retinal or disc NV often is trapped by the posterior vitreous hyaloid or cortex at its attachment points to the retina surface, resulting in the settlement of boat- or keel-shaped hemorrhage (Figure 3).

An exception is in the post-vitrectomized eye in which a diffused instead of clumped vitreous hemorrhage is usually seen.

Another exception is in a patient with nearly complete posterior vitreous detachment. Detection of new preretinal hemorrhages in previously treated eyes can indicate persistence, reactivation, and/or development of new NV requiring further management (Figure 2).

Conclusion

Careful attention is essential to the entire retina’s normal as well as abnormal features to maximize the detection of potentially consequential findings. However, if a complete examination is not possible in diabetic patients, pay close attention to the inferior retina. During slit-lamp fundus examination, patients are usually more cooperative when asked to look down for the OD to inspect the inferior retina. Additional ancillary testing like ultra-wid-field fundus photography and angiography can aid in detection of pathology. Timely inspection and detection as treatment of proliferative retinopathy is able to improve patient visual outcomes (Figure 4).

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.