- October digital edition 2022

- Volume 14

- Issue 10

Dacryostenosis illustrates the complexity of treating teary eyes

Katherine M. Mastrota, OD, FAAO, advises on how to diagnosis this condition and not fall prey to a “knee-jerk” dry eye diagnosis.

“My eyes are teary.” How many times in your clinical session do you hear this complaint from a patient?

As clinicians, we are well schooled in connecting this common complaint to ocular surface/dysfunctional tear/dry eye disease. It is important to consider, however, that numerous causes of patient ocular anatomical compromise can precipitate complaints of a “teary eye.”

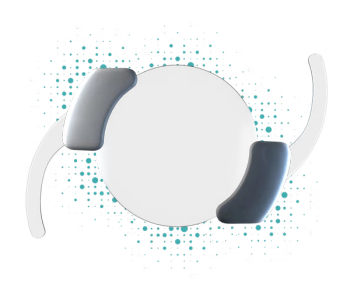

Dacryostenosis is an acquired or congenital condition that can cause epiphora and progress to dacryocystitis in children and adults. Dacryostenosis generally refers to an obstruction that can affect any part of the tear excretory system.1

Causes

The etiology of acquired dacryostenosis is multifactorial and not fully understood. Most commonly, it occurs from age-related stenosis of the nasolacrimal duct. Some cases are related to trauma, neoplasm, systemic disease, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy.1,2

Other causes include past nasal or facial bone fractures/sinus surgery that disrupt the nasolacrimal duct; inflammatory diseases (such as

Chronic inflammation may also cause fibrosis of the connective tissue fibers in the area of the lacrimal sac and nasolacrimal duct and loss of the blood vessels of the vascular plexus that surrounds the lacrimal sac and nasolacrimal duct contributing to malfunctioning of the tear outflow mechanism.1

Descending inflammation from the eye, or ascending inflammation from the nose, initiates swelling of the mucous membrane, remodeling of the helical arrangement of connective tissue fibers, malfunctions in the subepithelial cavernous body (vascular plexus) with reactive hyperemia, and temporary occlusion of the lacrimal passage.

As an example, repeated isolated occurrence of dacryocystitis leads to structural epithelial and subepithelial changes, which may result in either a total fibrous closure of the lumen of the efferent tear duct or to a nonfunctional segment in the lacrimal passage.3 However, in most cases of dacryostenosis, the cause is “involutional” and classified as “idiopathic.”

In addition, punctal stenosis can result in epiphora. The normal punctum is chronically exposed to irritant substances in the tear film. In most patients with punctal stenosis, there is inflammation caused by blepharitis, chronic exposure (ectropion), or an external irritant (including antihypertensive medications).

Punctal stenosis occurs in patients treated with chemotherapy agents for cancer.4 Interestingly, punctal stenosis has been reported as side effect of dupilumab 9and topical netarsudil used in glaucoma therapy.10

Infections involving the eyelid, such as those caused by typical HSV1, may also result in stenosis.5

Chronic blepharitis is a risk factor for punctal stenosis, as associated chronic inflammation would result in inflammatory membrane formation, conjunctival epithelial overgrowth, and keratinization around the walls of the punctum.

The pathogenesis suggested is chronic inflammation of the external punctum, leading to gradual fibrotic changes in the ostium and followed by progressive occlusion of the duct.6 Dry eye syndrome, which may be secondary to chronic blepharitis, has been suggested as an etiological factor for punctal stenosis.7

Diagnosing

Diagnosis of dacryostenosis is typically made through history and physical examination. The examination begins with an inspection of the eyelids, the lacrimal puncta, and the conjunctiva to rule out gross abnormalities.

The lower eyelid may present with mild redness and an increase in tear meniscus. Massage of the lacrimal sac may provoke reflux of tears and/or mucus onto the eye through the puncta.Other tests to consider include the following:

- Lacrimal irrigation: Complete reflux from the opposite punctum of the same eye is indicative of dacryostenosis or a common canalicular obstruction.

- Fluorescein dye disappearance test: After fluorescein has been placed in the fornix, the fluorescein remaining in the conjunctival cul-de-sac is examined with the cobalt blue light after 5 minutes. The amount of remaining fluorescein can be graded using a scale from 0 to 4, where 0 indicates no remaining dye and 4 indicates all the dye remains. In case of obstruction, a large amount of the dye persists or escapes over the lower eyelid and down the cheek. This is also compared to the opposite eye. Retention of the fluorescein indicates a delay in tear flow. If the result is normal, lacrimal drainage dysfunction is unlikely.8

Remember to observe the puncta and tear flow in your patients who report epiphora and not fall prey to the “knee-jerk” dry eye diagnosis.

References

Pezzoli M, Patel BC. Dacryostenosis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed September 1, 2022.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563132/ Mansur C, Pfeiffer ML, Esmaeli B. Evaluation and management of chemotherapy-induced epiphora, punctal and canalicular stenosis, and nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33(1):9-12.

doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000000745Paulsen FP, Thale AB, Maune S, Tillmann BN. New insights into the pathophysiology of primary acquired dacryostenosis. Ophthalmology. 2001;108(12):2329-2336.

doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00946-0Soiberman U, Kakizaki H, Selva D, Leibovitch I. Punctal stenosis: definition, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:1011-1018. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S31904

Jager GV, Van Bijsterveld OP. Canalicular stenosis in the course of primary herpes simplex infection. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997;81(4):332. doi:10.1136/bjo.81.4.329d

Bukhari A. Prevalence of punctal stenosis among ophthalmology patients. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2009;16(2):85-87. doi:10.4103/0974-9233.53867

Nadeem N, Patel BC. Punctal Stenosis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed September 1, 2022.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560578/ Wright MM, Bersani TA, Frueh BR, Musch DC. Efficacy of the primary dye test. Ophthalmology. 1989;96(4):481-483. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(89)32870-3

Lee DH, Cohen LM, Yoon MK, Tao JP. Punctal stenosis associated with dupilumab therapy for atopic dermatitis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32(7):737-740. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1711010

Meirick TM, Mudumbai RC, Zhang MM, Chen PP. Punctal Stenosis Associated with Topical Netarsudil Use. Ophthalmology. 2022;129(7):765-770. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2022.02.025

Articles in this issue

about 3 years ago

Making artificial tears less artificialabout 3 years ago

Orthokeratology is key to managing pediatric myopiaover 3 years ago

Refractive technologies encompass a rapidly changing landscapeover 3 years ago

Q&A: Exploring telehealth through DigitalOptometricsover 3 years ago

Current glaucoma treatments bring challengesover 3 years ago

Case study: Pigment epithelial detachment is observed, managedover 3 years ago

Debunking common ortho-k mythsNewsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.