- August digital edition 2023

- Volume 15

- Issue 08

Geographic atrophy is a major concern in eye health

You may be wondering: What is all this hype about geographic atrophy (GA)? If you are, let us look at the enigma.

Until recently, when most eye care professionals encountered a patient with

True, we discussed lifestyle modifications, dietary supplements, self-monitoring or remote monitoring of monocular vision, and low-vision aids, but we shied away from any meaningful discussion about dry AMD.

The success of anti-VEGF for wet or neovascular AMD (nAMD) had created the urgency to scrutinize each case to rule out these instances. We all understood from several sources including clinical trials that the sooner a patient was sent for treatment, the better the overall outcome.1

Once, I was asked by a colleague whether you could somehow convert patients with dry AMD to wet AMD so they can be treated. I thought he was humoring me, but he noticed the patients he was referring to retina specialists for nAMD were gaining vision whereas his dry AMD patients were losing vision. So, we knew these patients were losing vision but did not want to talk to them about it too much. What was the point? No treatment required no discussion.

Discussion

With the

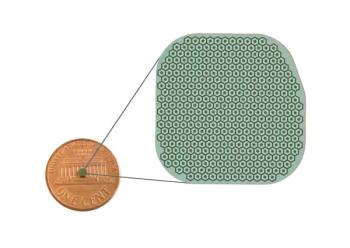

What is GA and how is it best detected? GA is defined as sharply demarcated atrophic lesions demonstrating loss of the outer retina including the photoreceptors, the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), and the underlying choriocapillaris (Figure 1). A new term for these lesions as detected by optical coherence tomography (OCT) is complete RPE and outer retina atrophy, whereas pre-GA lesions are known as incomplete RPE and outer retina atrophy.3

Although GA can be spotted clinically by ophthalmoscopy, early or small lesions can go undetected. Therefore, imaging schemes are crucial in precise detection and management of these lesions. Color fundus photography, fundus autofluorescence, and en face imaging including infrared or near-infrared each play a role in diagnosis and prognosis of these lesions (Figure 1).4 Additionally, OCT and OCT angiography (not depicted in Figure 1) have importance in detecting choroidal neovascularization in the presence or absence of GA.

Another question is how soon these lesions should be detected. We should consider several factors. Most patients with early GA can be asymptomatic with good Snellen acuity; therefore, relying on patient symptoms or the visual acuity level can be deceiving.

Furthermore, GA is progressive, irreversible, and eventually will cause reduced or lost visual function.5 These lesions often start in an extrafoveal or perifoveal area and grow on average 0.5 to 2.6 mm2 per year.5 Several sources highlight the fact that GA lesions can progress rapidly and usually in less than 3 years cause vision loss with drastic impact on activities of daily living including ability to drive and reading, with legal blindness ultimately resulting.6-8 Figure 2 is a case demonstrating the rapid succession of GA and declined vision.

Beyond the loss of precious visual function, there is a large human cost. These patients can experience anxiety and depression; they often withdraw from society9; they become dependent on others for transportation and living needs; and they will have difficulty tending to medical comorbidities, personal hygiene, and other aspects of life. Furthermore, there is danger of bodily harm such as injuries from falling.10

Conclusion

These considerations will make us realize that eye care providers should be vigilant in early detection and referral of patients with GA to prevent the growth of GA and reduce its disturbing effects on patients.6 The focus on GA is not only valid but way overdue.

References

1. Ying GS, Maguire MG, Daniel E, et al; Comparison of Age-Related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials (CATT) Research Group. Association of baseline characteristics and early vision response with 2-year vision outcomes in the Comparison of AMD Treatments Trials (CATT). Ophthalmology. 2015;122(12):2523-2531.e1. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.08.015

2. Prevalence of Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD). CDC. Updated October 31, 2022. Accessed July 27, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/visionhealth/vehss/estimates/amd-prevalence.html

3. Guymer RH, Rosenfeld PJ, Curcio CA, et al. Incomplete retinal pigment epithelial and outer retinal atrophy in age-related macular degeneration: classification of atrophy meeting report 4. Ophthalmology. 2020;127(3):394-409. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.09.035

4. Jaffe GJ, Chakravarthy U, Freund KB, et al. Imaging features associated with progression to geographic atrophy in age-related macular degeneration: classification of atrophy meeting report 5. Ophthalmol Retina. 2021;5(9):855-867. doi:10.1016/j.oret.2020.12.009

5. Fleckenstein M, Mitchell P, Freund KB, et al. The progression of geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(3):369-390. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.08.038

6. Chakravarthy U, Bailey CC, Johnston RL, et al. Characterizing disease burden and progression of geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(6):842-849. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.11.036

7. Holekamp N, Wykoff CC, Schmitz-Valckenberg S, et al. Natural history of geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration: results from the prospective proxima A and B clinical trials. Ophthalmology. 2020;127(6):769-783. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.12.009

8. Sunness JS, Gonzalez-Baron J, Applegate CA, et al. Enlargement of atrophy and visual acuity loss in the geographic atrophy from age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 1999;106(9):1768-1779. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90340-8

9. Williams RA, Brody BL, Thomas RG, Kaplan RM, Brown SI. The psychosocial impact of macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116(4):514-520. doi:10.1001/archopht.116.4.514

10. Wood JM, Lacherez P, Black AA, Cole MH, Boon MY, Kerr GK. Risk of falls, injurious falls, and other injuries resulting from visual impairment among older adults with age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(8):5088-5092. doi:10.1167/iovs.10-6644

Articles in this issue

over 2 years ago

Is it AMD or vitelliform?over 2 years ago

Managing cooperatively with patientsover 2 years ago

OCT is a crucial tool in glaucoma diagnosis and monitoringover 2 years ago

Historic signing at AOA: All about the 13% PromiseNewsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.