- March/April digital edition 2026

- Volume 18

- Issue 02

Integrating nutrition, oculomics, genetics, and photobiomodulation for macular degeneration

Understanding AMD pathophysiology through nutrition has helped shape the disease’s detection and management.

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that affects the macula; it is responsible for irreversible vision loss in individuals aged 55 and older and is the leading cause of irreversible central vision loss in older adults.1 Its complex nature arises from an interplay of environmental risks, metabolic stress, genetic predisposition, and age-related cellular decline. In recent years, advances in retinal imaging, data science, genetic sequencing, and therapeutic light-based interventions have reshaped the understanding of AMD pathophysiology and strategies for early detection and management. Four concepts—nutrition, oculomics, genetics, and photo-biomodulation—have advanced a more comprehensive approach to AMD care.

Nutrition and the retina

Nutrition has long been recognized as a modifiable risk factor for AMD, given the retina’s high metabolic rate and vulnerability to oxidative stress. Data from the landmark AREDS and AREDS2 clinical trials (NCT00000145; NCT00345176) demonstrated that specific combinations of micronutrients can slow progression from intermediate to advanced AMD. The AREDS2 formula—consisting of vitamin C, vitamin E, zinc, copper, lutein, and zeaxanthin—remains the most evidence-based nutritional intervention.2

The importance of lutein and zeaxanthin, 2 power-packed macular carotenoids highly concentrated in the fovea, lies in their ability to filter blue light and neutralize reactive oxygen species. Diets rich in leafy greens (ie, spinach, kale), colorful vegetables, and egg yolks help maintain macular pigment optical density (MPOD), which has been inversely linked to AMD risk. MPOD is a measurable modifiable biomarker defining the eye’s antioxidant capacity in the context of oxidative damage and retinal ischemia.3 Devices such as Zx Pro by EyePromise utilize technology to quantify MPOD. This provides additional data to design a personalized nutrition plan for these at-risk patients. In addition, omega-3 fatty acids, found in fatty fish, nuts, and seeds, help support photoreceptor health and reduce inflammation; however, the AREDS2 data did not show an additional benefit from supplementation alone.

Nutrition’s role extends beyond supplementation. The Mediterranean diet, rich in vegetables, fruits, legumes, whole grains, and healthy fats, is associated with a lower incidence of AMD and slower disease progression.4 Antioxidants, polyphenols, vitamins, and minerals collectively support retinal resilience. Metabolomics, along with the microbiome’s link to the gut-retina axis, is an additional influence on AMD development.5 Further, there are additional risk factors linked to sleep apnea, chronic vascular disease, UV exposure, smoking, and body mass index.6 Therefore, dietary and lifestyle modification remains a cornerstone of AMD risk reduction, particularly for individuals with early- or intermediate-stage disease.

Genetics: Understanding risk and individual variability

AMD is a quintessential example of a multifactorial disease influenced by both environment and genetics. AMD heritability is among the highest for common complex diseases. Findings from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified dozens of genetic variants associated with an increased susceptibility to AMD.7 The most prominent involve the complement pathway, especially variations in CFH and C3, which influence inflammation and immune regulation.8 Complement pathway variants (CFH, C3, C2/CFB) contribute to chronic low-grade inflammation at the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE)–Bruch membrane interface.9 CFH Y402H is a widely studied variant associated with increased deposition of complement fragments and drusen formation.10

Another major genetic contributor is the ARMS2/HTRA1 locus, strongly associated with progression to advanced AMD, particularly geographic atrophy, by influencing oxidative stress and inflammation. Individuals carrying both high-risk complement and ARMS2 variants are significantly more likely to develop visual consequences earlier.8

Visible Genomics’ AMDiGuard DNA Risk Test is a simple, in-office, noninvasive test that provides quick, clinically relevant results. However, genetic testing does not yet dictate specific therapies. Counseling should emphasize that genetics indicates risk, not destiny, and must be interpreted within the context of lifestyle and environment. However, genetic insights help explain differential disease trajectories and guide research into complement-inhibiting drugs, mitochondrial protection strategies, and personalized plans for emerging treatments. These genetic profiles can help influence preventive strategies, testing schedules, and treatment interventions.

Oculomics: Imaging as a window into systemic and ocular health

Regarding AMD, oculomics refers to the detailed information obtained from retinal imaging—especially high-resolution optical coherence tomography (OCT)—combined with artificial intelligence–driven analysis to extract biomarkers predictive of disease presence, progression, or systemic associations. In AMD, oculomics has transformed clinical understanding by allowing detailed visualization of drusen, subretinal drusenoid deposits, retinal pigment changes, and early neurodegenerative changes.

Machine learning models trained on OCT data sets can identify subtle structural changes years before clinical symptoms arise, facilitating early detection. This is particularly important because early AMD is typically asymptomatic. Predictive biomarkers such as hyperreflective foci, drusen volume, and photoreceptor layer integrity are emerging as powerful tools for classifying patients by progression risk.

Incorporating OCT and FAF-based risk scoring allows earlier detection and personalized follow-up intervals, especially in patients with metabolic or genetic risk factors. Several imaging biomarkers have strong predictive value for progression9:

- Drusen morphology and volume: Large, soft drusen and rapidly enlarging drusen volumes increase the risk of conversion to advanced AMD.

- Subretinal drusenoid deposits (SDD): Associated with impaired dark adaptation and choroidal thinning, SDDs correlate with higher conversion risk to geographic atrophy.

- Hyperreflective foci (HRF): Often representing migrating RPE cells or microglia, HRF signal impending atrophy.

- Choroidal thickness and vascularity: OCT-derived choroidal thinning reflects vascular compromise and mitochondrial stress in the outer retina.

- OCT angiography flow voids: Reduced choriocapillaris density precedes visible atrophy and is measurable in routine clinical practice.

Beyond AMD, this noninvasive testing has been used to detect systemic disease—such as cardiovascular risk (hypertension, stroke risk, atherosclerosis), neurological diseases (Alzheimer, Parkinson, multiple sclerosis), aging, inflammation, and metabolic disorders (diabetes)—illustrating the eye’s unique value as a biomarker-rich organ.11,12 In the context of macular degeneration, oculomics represents the intersection of eye care, data science, and precision medicine, enabling more personalized surveillance and therapeutic decision-making.

Photobiomodulation: Looking to the future with light as therapy

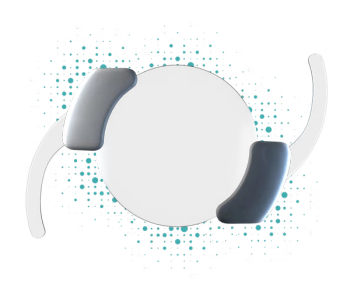

Photobiomodulation (PBM), also known as low-level light therapy, involves the application of specific wavelengths of visible to near-infrared light to influence cellular function. In retinal tissue, PBM is thought to enhance mitochondrial respiration, reduce oxidative stress, modulate inflammation, and improve metabolic efficiency—mechanisms particularly relevant to AMD, which involves mitochondrial dysfunction and chronic inflammation of the RPE.

The FDA-authorized therapy is the first noninvasive treatment for dry AMD. Clinical study data have shown that PBM may improve visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, mitochondrial function in the RPE, and photoreceptors and drusen characteristics in early or intermediate AMD, and is less likely to develop geographic atrophy.13,14 Treatments typically use specific wavelengths of visible to near-infrared light between 590 and 850 nm to stimulate cytochrome-c oxidase activity, thereby enhancing ATP production and reducing inflammatory signaling. Although the results are promising, treatment appears to be most effective early in the disease, before widespread atrophy develops. Optometrists implementing PBM must consider energy dose, wavelength-specific effects, contraindications, and maintenance protocols. Regulatory approval varies by region, but interest in PBM continues to grow as a noninvasive, potentially disease-modifying approach.

A wellness-rounded approach to AMD management

AMD management increasingly relies on integrating nutrition, genetics, and oculomics into a holistic framework, expanding the role of optometrists in AMD prevention and management. Nutritional optimization targets oxidative stress, genetics highlights susceptibility and potential biological pathways, oculomics provides real-time biomarkers for monitoring, and PBM offers an emerging therapeutic modality aimed at cellular repair.

Taking these together, AMD treatment represents a shift from late-stage complications to proactive, personalized management. As research advances, individuals with genetic risk may be monitored using oculomic biomarkers, guided in targeted nutritional interventions, and potentially supported with PBM to preserve retinal function long before severe damage occurs.

References

Barreto P, Farinha C, Coimbra R, et al. Interaction between genetics and the adherence to the Mediterranean diet: the risk for age-related macular degeneration: Coimbra Eye Study Report 8. Eye Vis (Lond). 2023;10(1):38. doi:10.1186/s40662-023-00355-0

Age-Related Eye Disease Studies (AREDS/AREDS2). National Eye Institute. Updated October 22, 2025. Accessed December 15, 2025. https://www.nei.nih.gov/research/clinical-trials/age-related-eye-disease-studies-aredsareds2

Masri A, Armanazi M, Inouye K, Geierhart DL, Davey PG, Vasudevan B. Macular pigment optical density as a measurable modifiable clinical biomarker. Nutrients. 2024;16(19):3273. doi:10.3390/nu16193273

Gastaldello A, Giampieri F, Quiles JL, et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean-style eating pattern and macular degeneration: a systematic review of observational studies. Nutrients. 2022;14(10):2028. doi:10.3390/nu14102028

Rowan S, Jiang S, Korem T, et al. Involvement of a gut-retina axis in protection against dietary glycemia-induced age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(22):E4472-E4481. doi:10.1073/pnas.1702302114

Risk factors. Age-related macular degeneration: diagnosis and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2018. NICE Guideline No. 82. Accessed December 15, 2025.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536467/ Fritsche LG, Igl W, Bailey JNC, et al. A large genome-wide association study of age-related macular degeneration highlights contributions of rare and common variants. Nat Genet. 2016;48(2):134-143. doi:10.1038/ng.3448

Colijn JM, Meester-Smoor M, Verzijden T, et al; EYE-RISK Consortium. Genetic risk, lifestyle, and age-related macular degeneration in Europe: the EYE-RISK Consortium. Ophthalmology. 2021;128(7):1039-1049. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.11.024

Heesterbeek TJ, Lorés-Motta L, Hoyng CB, Lechanteur YTE, den Hollander AI. Risk factors for progression of age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2020;40(2):140-170. doi:10.1111/opo.12675

Seddon JM, Reynolds R, Rosner B. Peripheral retinal drusen and reticular pigment: association with CFHY402H and CFHrs1410996 genotypes in family and twin studies. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50(2):586-591. doi:10.1167/iovs.08-2514

Zekavat SM, Jorshery SD, Rauscher FG, et al. Phenome- and genome-wide analyses of retinal optical coherence tomography images identify links between ocular and systemic health. Sci Transl Med. 2024;16(731):eadg4517. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.adg4517

Cheng H, Sarnat JA, Walker DI, et al. Oculomics meets exposomics: a roadmap for applying multi-modal ocular biomarkers in precision environmental health research. Exposome. 2025;5(1):osaf013. doi:10.1093/exposome/osaf013

Boyer D, Hu A, Warrow D, et al. LIGHTSITE III: 13-month efficacy and safety evaluation of multiwavelength photobiomodulation in nonexudative (dry) age-related macular degeneration using the Lumithera Valeda Light Delivery System. Retina. 2024;44(3):487-497. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000003980

Rodriguez DA, Song A, Bhatnagar A, Weng CY. Photobiomodulation therapy for non-exudative age-related macular degeneration. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2025;65(1):47-52. doi:10.1097/IIO.0000000000000543

Articles in this issue

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.