- May digital edition 2020

- Volume 12

- Issue 5

Optometry’s Apollo 13 moment during COVID-19

For ODs during the COVID-19 pandemic, failure is not an option.

In retrospect, NASA probably should have skipped from 12 to 14 like many hotel elevators do.

For a while, it seemed like everything that could go wrong on Apollo 13 did: an explosion during a routine “stirring” of the oxygen tanks of the Apollo Service Module (SM) left a gaping hole in its side, leading to a cascade of life-threatening and complex conundrums no one had ever conceived of, much less planned or simulated for.

Hopes of landing on the moon vanished. The new mission was to somehow, in the words of a common military slogan, “improvise, adapt, and overcome,” and bring Astronauts Jim Lovell, John Swigert, and Fred Haise home.

Related:

The cool heads of the flight crew, their fellow astronauts, Mission Control (MC) staff, and perhaps most importantly their leader, Flight Director Gene Krantz, combined to form a hive mind which buzzed with creativity, focus, and synergy. A small army of NASA engineers and contractors, wearing short-sleeve white shirts, skinny black ties, and wielding pencils and slide rules like weapons of war, crafted solutions seemingly from thin air, each more improbable than the last. Together they reached the boundaries of their knowledge and training and blew past them to perform feats of derring-do that defied the gravity of human limitations.

One jerry-rigged jewel stood out: a life-saving carbon dioxide (CO2) scrubber, fashioned only from materials available to the astronauts onboard, including, naturally, duct tape and cardboard. The device, dubbed “the mailbox,” enabled the different-shaped CO2 filters from the CM and LM to work in tandem, essentially fitting the proverbial “square peg fit in a round hole.”

Related:

I was in second grade when the events of Apollo 13 occurred in April 1970 and barely remember it. Still, when the full import of the COVID-19 pandemic hit me on the evening of March 15, I thought of Apollo 13 and how we could apply the same lessons of courage, creativity, resiliency and perseverance in humanity’s latest “darkest hour.”

There is one vital difference between the pair of dire straits. Apollo 13 was blindsided by a random stroke of bad luck fueled by a small design flaw that had been overlooked. We, on the other hand, knew what was coming because we could see our peril approaching from thousands of miles away.

Related:

Optometry, we have a problem!

It didn’t take the sound of an oxygen tank exploding for me to know that optometry had a problem on the evening of March 15-just a little “ding.” It was a text from our current fourth-year University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) extern: “UAB has suspended all non-emergent and routine care and pulled students off rotations and externships.”

I checked my inbox for confirmation. I found it, but I had to read it several times before I believed it and the full impact hit home.

For a health system with the size and influence of UAB to pull the plug on all non-emergent and elective procedures and appointments, including routine dental and ophthalmic outpatient care, there had to have been a disruptive and seismic healthcare event, especially considering the small number of COVID-19 cases in Alabama, at the time. I knew they were not acting in isolation and there would soon be a tsunami of major healthcare systems and academic medical centers across the country acting in concert.

Related:

Given the close affiliation of our Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center in Birmingham with UAB, I surmised we would soon follow the same course. I called a co-worker and discussed the possibility. We brainstormed on how to start changing the shape and function of our clinics to conform to a mandate that would surely be coming down soon from the C-suite.

Less than 48 hours later, we had our orders to pare back our clinics to only urgent/emergent care and implemented them. Most institutional-based ODs followed a similar path. In integrated, hierarchal healthcare systems, employees do what their leadership tells them.

For independent ODs, however, it took a few more days of debate, along with guidance from the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO), the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), the American Optometric Association (AOA), numerous state optometry boards, and in some case, orders from state governors, before a consensus developed and the realization hit home that routine eye care, as we knew it, would cease for the time being.

Related:

It was interesting to watch the debate on various optometry social media platforms. It was a confusing time, and many were understandably shaken and confused.

There were those who said, “We can’t close our practices--#BeADoctor!” Others argued that “being a doctor” meant taking public health warnings seriously and dutifully performing our role in minimizing virus transmission.

It was apparent to the latter group, and eventually most others, that “less essential” health professions and specialties requiring close doctor-patient working distance like optometry, dentistry, and ophthalmology, were at risk of droplet transmission.

Optometry does many things well, but in general, we are not experienced in or accustomed to stringent infection control measures.

Related:

Despite our best efforts, it is hard to completely disinfect all equipment and exam rooms in between patients, as well as the eyeglass frames patients handle and try on. The risk of coronavirus transmission through tears and ocular secretions was small with the appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE), but a possibility, nonetheless.

Most of us ODs like to avoid gloves and masks if possible-they are barriers between us and patients that might make us look less friendly and approachable (two of our many strengths!). Besides, aren’t those for other “messier” health professions and specialties?

I believe we found the right balance: recognizing the need to improvise means of attending to the basic vision and ocular health needs of patients who were quarantined or sheltered in place while reserving in-patient exams for urgent cases and patients with more fragile ocular disease for whom a prolonged exam delay would mean increased risk to their sight.

Related:

Optometrists took a step back, realized the proper role of support they could play in the COVID-19 pandemic, and powered down, despite, in many cases, grave financial risk to themselves, their employees, and their families.

Our profession, with its longstanding tradition of independence and autonomy-and the infighting that can sometimes accompany it-was, in the span of 48 hours, essentially marching lockstep in a responsible and medically ethical direction.

It was the most remarkable scene I had witnessed in 30 years of practice. We showed, like the crew of Apollo 13, that we were made of “the right stuff.”

Related:

We gotta turn everything off, now!

Per the cinematic retelling of the story, this was the urgent warning from a young engineer to Flight Director Krantz and his team as they debated how to get the crew back to Earth safely. None of it would matter, he said, if the crew didn’t preserve every amp of energy they could, down to the bare essential functions needed to survive.

First, they had to power down the control module designed to carry three astronauts to the moon and back and move to the lunar module (LM), now a “life boat,” whose designed purpose was to carry a pair of crew members to the moon and back to the CM over two days.

Could the three survive in the LM with minimal life support? Would they be able to steer the LM toward Earth while executing the “long burn” of the LM’s descent engine needed to give them the necessary course bearing and boost to go the distance?

Related:

Even if they were able to accomplish those improbable feats, would they be able to power up the CM in time to reenter the earth’s atmosphere (all the while preserving those precious amps), and would the CM have the structural integrity after the initial explosion to survive the searing heat of reentry?

No one knew the answers to those questions because no one had ever considered such an outrageously “impossible” scenario to begin with.

Many ODs find themselves in a similar perilous position in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic; trying to figure out ways for their practices, employees, and families to financially survive this undetermined period, and at the same time, practice the methods of safe hygiene, infection control, social distancing, and self care needed to prevent themselves and all their contacts from becoming another COVID-19 statistic.

Related:

With all due respect, sir, I believe this is going to be our finest hour

Actor Ed Harris delivers this stirring line after overhearing a couple of NASA officials already envisioning failure and how the public will perceive and judge NASA in its wake. His characterization of Flight Director Krantz was of a man who would tolerate no doomsaying and instead rose above panic and groupthink by leaning into solutions and choosing to believe his “mission impossible” would succeed.

Similarly, I have already seen encouraging signs that ODs are up to the task of mapping out their own paths through this dangerous odyssey. We have a seminal opportunity to unify, band together, and forge a stronger yet more flexible profession in the flames of the COVID-19 pandemic, regardless of practice mode and philosophy.

Even in the midst of the painful process of furloughing employees, many independent ODs have sought to ease the shock by extending benefits, and in some cases even salaries, for as long as possible, and helped guide their staffs through the process of obtaining unemployment benefits and financial assistance from the various federal COVID-19 relief packages recently passed by Congress.

Related:

ODs, their professional organizations, practice management consultants, ophthalmic industry partners, staff, and patients have become more transparent with each other and opened new, improved lines of communication.

Examples of this are:

– The AOA’s quickly convened town hall on coding and practicing telemedicine offered to all ODs during the first week of the shutdown as well as its ongoing assistance in guiding members through federal COVID-19 financial relief packages

– The two-night town hall hosted by Gary Gerber, OD, and his radio show “The Power Hour,” which brought together industry partners to encourage ODs and provide sound advice on how to survive and prepare for restarting private practices post-pandemic

– The dissemination of critical information and opportunities to commiserate, encourage, and brainstorm with colleagues facilitated by social media platforms such as ODs on Facebook and ODwire

Related:

Many ODs are being forced by circumstance to improvise and reimagine how to deliver care during this trial by fire and after it is over.

Few independent ODs have ever had to triage before because their resources have usually exceeded demand. But with most practices closed to routine care and available only for urgent/emergent care, ODs are learning how to balance public health mandates to decrease in-person visits with their patients’ ongoing optical and ocular health needs.

A vital key in this process has been the sudden interest in and adoption of ocular telehealth and other means of digital care and product delivery.

Many in our profession have been resistant to telemedicine, tightly gripping the rigid status quo notion that the “standard of care” must always entail “the full works” at an in-person exam.

There is another possibility, however: a standard that flexes and adapts to the unique circumstances of patients, differences in access to care, and sudden disruptive societal shifts like pandemics to ensure the critical needs of the moment are met and other, less urgent conditions are addressed in an appropriate timeframe and manner.

Related:

Our medical colleagues in various specialties, including ophthalmology, have not hesitated to move forward in the practice of telemedicine. Also, ODs in federal and other institutional settings have been using telemedicine for years, including teleretinal screening for diabetic retinopathy, ocular diseases, and other forms of ocular telehealth, both synchronous (live televideoconferencing) and asynchronous (store and forward), to help patients receive appropriate care.

Telemedicine can not and will likely never be able to deliver every service and treatment that a patient may need, but it is a valid and proven means of triaging and managing immediate concerns in a responsible manner and identifying conditions and treatments that should be delivered at in-person exams. Telemedicine can increase quality eyecare access when demand is greater than resources and in critical times like during a pandemic when we must limit in-person care.1

As telemedicine becomes increasingly necessary, ODs must gain confidence in remote diagnostic and treatment decisions previously made only after in-person exams.

Related:

Regardless of in-person or online exams, data is inherently “incomplete,” a fact ODs who have practiced the “medical model” for years will acknowledge. What matters most in both cases is the use of sound clinical judgement to ensure that immediate problems and potential ophthalmic conditions are identified and the right level of care is delivered, at the right time, by the right practitioner.

These austere times force us to stretch beyond our previous comfort zones, reconsider previous ways of thinking, and try novel methods of care delivery. If you feel you are taking on “too much risk” by using telemedicine, consider the providers who are working on the front line of the pandemic with limited data, making life and death decisions on the fly. The risks of responsibly using telemedicine to deliver eye care are less than the risks of not using telemedicine at a time like this.

I’m encouraged to see so many ODs in these first few weeks of crisis embracing and utilizing telemedicine platforms, perhaps for the first time. Ocular telehealth will continue to evolve in its protocols and technology, further improving accuracy and correlation with face-to-face exams.2

Its impact will extend far beyond the time when herd immunity and an inevitable COVID-19 vaccine ends the current pandemic.

Related:

A successful failure

Apollo 13 was branded “a successful failure” in that it failed in its mission objectives and nearly resulted in catastrophic loss of life but ultimately achieved the most important criterion of success- bringing the crew home safely.

It is impossible to know, at this time, where our present perilous moment will lead us. It is safe to say, though, much of what we have grown accustomed to in our practices has changed forever.

Some creative, entrepreneurial spirits will have the energy and perseverance to “jump start” their private practices, rise from the ashes, and become stronger than ever before.

There will always be room in optometry for hardy souls to carve out their own paths, offering specialty care and a level of service that is rarely matched by other practices more tailored to the average needs of patients.

Others, understandably, will seek the stability and shelter of employment. Among many mid- to late-career ODs, the current trend of selling to private equity companies and continuing to practice as employees may accelerate due to the anticipated devaluation of private practices. For better or worse, vertical integration will increase.

The emotional scars of COVID-19 on the public will never completely fade. Our patients will emerge from this time with a heightened awareness of infectious disease transmission, and they will demand proof we are following best practices of social distancing and sanitation from the start of the patient care experience to the finish, beginning with the waiting room, continuing with exam areas and equipment, and into the dispensary.

More by Dr. Brown:

They will expect the option of remote and small footprint “low-” to “no-touch” services and products, a niche that ocular telehealth and online ordering and delivery can help fill. “Curbside delivery” of ophthalmic products may even evolve into “curbside consult” care like “drive-thru” fever clinics that have popped up recently.

Patients will return for eye care when this is over, but they may prefer not to be forced to come into a physical office every time they need assistance. ODs will need to factor these expectations into business restarts.

There is a constant we can count on, however: people will need to see their best in an increasingly complex and challenging world, and ODs are the professionals best suited to deliver the services and products that will safeguard vison and improve it.

There is no choice but to “work the problem” of the COVID-19 pandemic and keep moving forward.

We must “fit a square peg in a round hole,” and as Apollo 13 Flight Director Krantz put it, “Failure is not an option.”

More by Dr. Brown:

References:

1. Maa Ay, Medert CM, Lu X, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of technology-based eye care services: the technology-based

eye care services compare trial part I. Ophthalmology. 2020;127:38-44.

2. Maa Ay, Medert CM, Lu X, et al. The impact of OCT on diagnostic accuracy of the technology-based eye care services protocol: part II of the technology-based eye care services compare trial. Ophthalmology. 2020;127:544-549.

Articles in this issue

over 5 years ago

Key elements to know about MIPS in 2020over 5 years ago

Masquerading maculopathy: The importance of correct diagnosisover 5 years ago

Misdiagnosis when clinical findings don’t make senseover 5 years ago

How to differentiate CTK from DLK in post-surgical patientsover 5 years ago

Time in range as an alternative to HbA1cover 5 years ago

Engineer a specialty contact lens practiceover 5 years ago

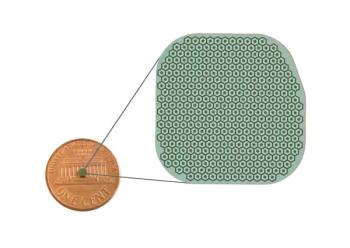

Elevate standard of care with artificial intelligenceover 5 years ago

Telemedicine in the face of COVID-19Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.