- November/December digital edition 2025

- Volume 17

- Issue 06

Ortho-k: More than meets the eye to control myopia progression

An effective but underused resource with positive benefits for patients with myopia.

Orthokeratology (ortho-k) has been around for a while, with roots dating back to the 1960s, but its beneficial results have only begun to be appreciated relatively recently. The technology underwent steady development in the 1980s and 1990s, but later advances in computer technology and contact lens refinements brought ortho-k to the forefront.1

“Ortho-k is indeed an underused resource. The science behind the technology for controlling myopia is rock solid, and my patients love it,” commented Thanh Mai, OD, FSLS, who has used the procedure to manage myopia in more than 1000 patients. “In my clinical experience, ortho-k is one of the most effective myopia treatments and is my first choice,” he said. Mai practices with Insight Vision in Costa Mesa, California.

“Currently, ortho-k is experiencing slow, steady acceptance in the US as it becomes more visible both to the public and vision practitioners,” he said.

Eye clinicians have only minimal working knowledge of the technology and are not yet well trained in implementing ortho-k in practice, hence its slow acceptance. Although managing myopia using ortho-k is discussed in optometry school, the number of patients who are potential candidates in clinical practice is limited, and physicians have not yet gained sufficient experience managing myopia using ortho-k. In addition, cost may be a factor.

Some demographics have shown that ortho-k is especially utilized by certain populations in the US who are more likely to have been exposed to information about this method of myopia management. In addition, major metropolitan areas, rather than rural areas, tend to be more fertile ground for growing an ortho-k practice.

Technologic development

Ortho-k began with the observational use of rigid lenses in the 1940s and 1950s to correct vision. The deliberate use of modern ortho-k lenses began in the 1960s with George Jessen's introduction of the “Orthofocus” lenses.1,2 The 1990s saw significant advancements, including the development of the corneal topographer and the creation of modern reverse-geometry lenses, which led to widespread availability and FDA approval of the use of ortho-k lenses during sleep in 2002.2

Looking back at the history of the technology, data from early clinical studies of ortho-k demonstrated variable outcomes, with no consensus on the most appropriate lens design or on the number and timing of the lens refittings.3 The first comprehensive study was conducted from 1976 to 1978,4-11 and later studies took place in 1980 and 1983.12,13

Although the experimental design and breadth of these studies varied, they were nevertheless reasonably consistent in their overall findings. As a result of the findings from those controlled clinical studies, it was established that the refractive effect was unpredictable, variable, and slow. Regression was rapid, so ongoing lens wear was necessary to maintain the effect, and significant corneal astigmatism often developed if lens centration was not properly controlled.2

Two scientific advances ushered in the modern ortho-k era in the mid-1990s: computerization that led to greater control over lens lathing and dramatically improved measurement of corneal topography, and improvements in polymer technology that resulted in the development of gas-permeable contact lens materials.2

Data from 2 studies in 198914 and 199215 showed that reverse-geometry lens designs, which resulted from computerized lathing, could stabilize flat-fitting lenses. Reverse-geometry lenses have secondary curves that are steeper than the radius of the back optical zone. When used in a flat-fitting rigid contact lens, this enabled peripheral realignment with the cornea in what would otherwise be a poor-fitting lens with excessive edge lift. When this was applied to ortho-k, larger steps in lens flattening were possible between successive lenses without compromising the lens fit and centration. This new approach in ortho-k lens fitting was referred to as “accelerated orthokeratology” because it provided a rapid onset, defined as within a few days, of effects that had previously taken weeks or months to achieve.2

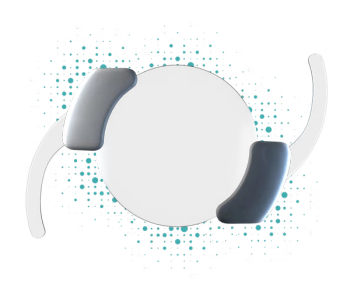

How ortho-k works

Ortho-k contact lenses, worn mostly at night to correct myopia, temporarily reshape the cornea to improve vision. Those improvements can be reversed but can also be maintained if patients continue to wear the lenses as directed,16 according to the American Academy of Ophthalmology.

The lenses work by flattening the center of the cornea, which changes the refraction of the light entering the eye. These rigid, gas-permeable lenses can reshape the cornea and allow sufficient oxygen to reach the eye.16

Patients are instructed that wearing the lenses at night for 2 weeks or longer may be required to achieve the maximal vision correction; however, significant visual improvement can occur in some patients within days. In data from clinical studies of FDA-approved ortho-k lenses, most patients achieved 20/40 vision or better.16

The benefits of maintaining myopic control are the lowered risk of developing serious ocular disease, such as pathologic myopia, and improvements in lifestyle.

Implementing ortho-k in private practice

Mai finds that patient information brochures that describe ortho-k have helped grow his practice. In most cases, the patients’ parents express surprise that such a method exists.

Among parents who opt to treat their children with ortho-k, the first follow-up appointment after the patients began wearing the lenses invariably results in the wow factor. The children can now read the lower lines of the Snellen chart, which is in contrast to not being able to read the “big E” unaided during the initial examination, Mai recounted.

Mai reported that most patients for whom ortho-k is prescribed in the US are between 8 and 16 years of age.

“I certainly have treated patients who are 7 years and younger, but in my experience, these patients or their parents may delay contact lens fitting until they are a little older,” he commented.

Case report

Mai described the case of a 9-year-old boy who is under treatment for myopia management.

“The patient was not yet myopic at 5 years of age but had many of the risk factors for myopia; that is, very low hyperopia for his age, Asian descent, and 2 myopic parents,” he reported.

Mai started atropine therapy when the patient’s refractive state was emmetropic before the development of myopia, with the goal of preventing the disease from developing. The patient began using MiSight contact lenses (CooperVision) at age 6 and started ortho-k when he was 7 years old. The patient continues treatment with ortho-k and has 2 D of myopia, and Mai believes that the level of myopia would have been much worse had he not treated him when he was still premyopic.

“The earlier the treatment starts, the better the outcomes may be later,” he stated.

Mai believes that prescribing myopia management early on for this patient was more effective than waiting until he developed more mild to moderate myopia.

Take-home messages for clinicians

Mai highlighted the most important points when considering the management of patients with myopia:

Myopia is a disease. “Many doctors may think of it only as a refractive error and not an ocular disease. Myopia is also a progressive disease that can be stopped or slowed.”

Myopia should be treated like any other ocular disease. “Physicians should establish a mindset that myopia should be considered a disease, just like glaucoma, that is worth treating. If this can be established, it is a win-win for patients and physicians.”

“As long as most doctors believe that myopia is a disease, some kind of treatment is better than no treatment. It doesn’t matter if treatment is with atropine, ortho-k, the forthcoming myopia glasses, or multifocals, just do something for the 90% of children who are initially left untreated,” Mai advised.

References

Lipson MJ, Koffler BH. The history and impact of prescribing orthokeratology for slowing myopia progression. Eye Contact Lens. 2024;50(12):517-521. doi:10.1097/ICL.0000000000001123

Gifford P. Orthokeratology. Efron N, ed. In: Contact Lens Practice. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2017:296-305.e2.

Carkeet NL, Mountford JA, Carney LG. Predicting success with orthokeratology lens wear: a retrospective analysis of ocular characteristics. Optom Vis Sci. 1995;72(12):892-898. doi:10.1097/00006324-199512000-00007

Kerns RL. Research in orthokeratology: part I: introduction and background. J Am Optom Assoc. 1976;47(8):1047-1051.

Kerns RL. Research in orthokeratology: part II: experimental design, protocol, and method. J Am Optom Assoc. 1976;47(10):1275-1285.

Kerns RL. Research in orthokeratology: part III: results and observations. J Am Optom Assoc. 1976;47(12):1505-1515.

Kerns RL. Research in orthokeratology: part IV: results and observations.

J Am Optom Assoc. 1977;48(2):227-238.Kerns RL. Research in orthokeratology: part V: results and observations––recovery aspects. J Am Optom Assoc. 1977;48(3):345-359.

Kerns RL. Research in orthokeratology: part VI: statistical and clinical analyses. J Am Optom Assoc. 1977; 48(9):1134-1147.

Kerns RL. Research in orthokeratology: part VII: examination of techniques, procedures and control. J Am Optom Assoc. 1977;48(12):

1541-1553.Kerns RL. Research in orthokeratology: part VIII: results, conclusions, and discussion of techniques. J Am Optom Assoc. 1978;49(3):308-314.

Binder PS, May CH, Grant SC. An evaluation of orthokeratology. Ophthalmology. 1980;87(8):729-744. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(80)35171-3

Polse KA, Brand RJ, Vastine DW, Schwalbe JS. Corneal change accompanying orthokeratology: plastic or elastic? results of a randomized controlled clinical trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 1983;101(12):1873-1878. doi:10.1001/archopht.1983.01040020875008

Wlodyga RJ, Bryla C. Corneal moulding; the easy way. Contact Lens Spectr. 1989;4:14-16.

Harris DH, Stoyan N. A new approach to orthokeratology. Contact Lens Spectr. 1992;7:37-39.

Mukamal R. What is orthokeratology? American Academy of Ophthalmology. April 23, 2023. Accessed October 29, 2025. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/glasses-contacts/what-is-orthokeratology

Articles in this issue

about 1 month ago

Managing glaucoma in an ophthalmic practice: An artful approachabout 1 month ago

“Family business?” Navigating the business of treating familyabout 2 months ago

How to put wearable virtual reality technology to work in your practiceabout 2 months ago

The mechanics of presbyopia: From muscle movement to functional visionabout 2 months ago

Optometric and ophthalmic forces unite at EyeCon 2025about 2 months ago

The A to Zzzs of ocular health2 months ago

The microbiome in diabetes and DRNewsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.