- November/December digital edition 2025

- Volume 17

- Issue 06

Retinal ganglion cells: What they can tell us and why we should listen

RGCs can offer a window into confirming eye condition diagnoses.

People can’t see without them, and yet they are often overlooked in routine ophthalmic examinations. Clinicians spend valuable time grading a cup-disc ratio and staring intently for a foveal light reflex, but the retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) are the eye’s connection to the brain, so giving them a good look makes sense.

The macula houses approximately 50% of RGCs, and there are about 3 of them per photoreceptor.1 The RGC consists of a dendrite tree, cell body, and axon (ie, the retinal nerve fiber layer [RNFL]).2 The dendrite tree receives input from retinal bipolar and amacrine cells. From there, the signal goes to the cell body, which is located within the innermost part of the retina, called the ganglion cell layer (GCL). RGC axons then carry the signal through the optic nerve, optic chiasm, and optic tract before finally synapsing in the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN). Optic radiations continue the transfer from the LGN to the visual cortex.

The RGCs play a huge role in this visual pathway. Also important to remember is that RGCs are central nervous system neurons.2 Hence, they cannot regenerate by cell division, and any damage to them is irreversible. Therefore, their assessment is vital. Analyzing them can offer valuable insight into various ophthalmic conditions or detect previously unknown systemic anomalies.

Glaucoma

For years, the visual field stood as a major test for diagnosing and monitoring glaucoma, and it remains the standard of care today, although it has its faults. Then came optical coherence tomography and the RNFL scan, complete with a sine wave graph and street-light coloring to indicate RNFL thickness when compared with a reference database. Like the visual field test, the RNFL also has flaws. In 2016, Chen and Kardon addressed some of these shortcomings in their original work on the subject.3 These include segmentation errors, effects of refractive error and axial length, and peripapillary atrophy. In addition, the tilted myopic disc can be a nightmare to assess with the RNFL. When these challenges present, scanning the GCL can provide additional data.

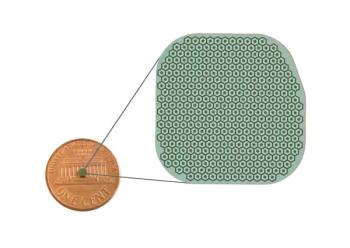

Glaucomatous damage typically starts in the macular vulnerability zone, which is an area that extends from the optic nerve’s inferior portion of the temporal quadrant to the temporal portion of the inferior quadrant.4 Therefore, the pattern of GCL insult will usually take on a characteristic appearance (Figure 1). Lee et al introduced the temporal raphe sign to distinguish between glaucomatous and nonglaucomatous thinning.5 They defined it as a straight line longer than one-half of the length between the inner and outer annulus in the temporal elliptical area of the macular ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer (mGCIPL) complex (Figure 1).5

Another reason for getting GCL scans in glaucoma is the structure-function connection, which tends to have a tenuous alignment. Having another objective test can be helpful. Several years ago, Tsamis et al presented the structure-structure (S-S) metric, which is based on the agreement between GCL and RNFL abnormalities.6

Retrograde degeneration

To understand this process, recall the visual pathway as described above. Nasal to the macula RGC axons leave the optic nerve and cross at the optic chiasm, joining the temporal to the macula RGC axons from the contralateral side. Once united, they form the optic tract and synapse at the LGN and then go to the visual cortex. Therefore, like a visual field, pathological changes that target the chiasmal and postchiasmal regions may generate a GCL defect that respects the vertical midline. In this author’s clinical practice, the 2 most common conditions that produce this type of defect are pituitary macroadenoma and stroke.

Pituitary macroadenoma

Ask any optometry student, resident, or maybe even practitioner what the most common visual defect is with a pituitary macroadenoma, and the response would likely be a bitemporal hemianopsia. This is what they have been taught, and, unfortunately, it is an incorrect answer. In a 2015 article by Lee et al, they described the classic finding of bitemporal hemianopsia as “a myth” and “exceedingly uncommon.”7 In their study, out of 89 patients with visual field defects, only one displayed a bitemporal hemianopsia. Also, since nonsecreting pituitary adenomas tend to affect older males, an early superior bitemporal visual defect may be mistaken for lid hooding. Therefore, analyzing the GCL may be helpful in patients with a pituitary macroadenoma (Figure 2).

Stroke

The so-called silent, or asymptomatic, stroke is by far more common than its symptomatic counterpart. In fact, for every symptomatic stroke, there could be up to 10 people with silent brain infarcts.8 It is the most common incidental finding on neurological imaging.8 Estimates put its presence in nearly 1 in 5 stroke-free older adults.9 Having a silent stroke is certainly something to scream about, since it doubles a patient’s risk for having another incident.9

Like traditional neurological imaging, GCL analysis represents another type of analysis, as RGCs are part of the central nervous system. There, the GCL scan may uncover a history of silent infarct similar to a radiologist discovering one in an asymptomatic patient (Figure 3). Doing so opens the possibility for risk reduction of a second stroke through coordination with the patient’s primary care provider.

Nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAAION)

In middle-aged and older adults, the most common acute optic neuropathy is nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAAION).10 Characterized by acute vision loss and optic nerve swelling, the condition affects around 2 to 10 per 100,000 people.11 Clinicians encountering NAAION will typically order a visual field test and an RNFL scan, along with other appropriate tests, when there is a suspicion of the more perilous arteritic anterior ischemic neuropathy, which is beyond the scope of this article. Practitioners expecting to find an altitudinal visual defect may be disappointed, as this is not the most common result, but rather an inferior nasal defect.12 Therefore, don’t fall for the pathognomonic result of an inferior altitudinal defect.

Since NAAION produces optic nerve edema, the RNFL will undoubtedly appear thicker at presentation when compared with the reference database. However, remember that the RNFL scan simply measures thickness. Therefore, at follow-up, avoid telling the patient they are getting better. The only thing that can be said is that the RNFL thickness has decreased, but measuring tissue loss from baseline at this point is not possible. A better method for detecting early structural change is the GCL scan, since the RGCs are less likely to be affected by edema.13,14 Although the RNFL will undoubtedly show eventual loss, the GCL may provide a much earlier biomarker in predicting a permanent deficit. GCL thinning occurs prior to RNFL thinning and can be seen as early as 1 month.14 Also, unlike the visual field in patients with NAAION, the GCL thinning will typically be altitudinal (Figure 4).15

Optic neuritis and multiple sclerosis

Optic neuritis (ON) is an inflammation of the optic nerve and, unlike NAAION, is the most common optic neuropathy in young adults.16 Typical or demyelinating ON is the most common type.17 Only about one-third of patients with ON have optic nerve edema, and the GCL loss tends to be diffuse with no specific pattern.15 The landmark Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial found that within 15 years, 50% of patients with ON developed multiple sclerosis (MS).18

Similar to NAAION, the GCL may show thinning within 5 weeks of an acute ON vs 3 months for the RNFL.19 GCL thinning may also occur in patients with MS without a documented history of optic neuritis (Figure 5).19 Some researchers note that following patients with MS long-term reveals an inverse relationship between disease duration and GCL thickness. Specifically, they found an estimated rate of thinning of between –0.34 and –0.53 μm/year, which was almost 50% faster than healthy controls (–0.20 μm/year).19

Can you hear me now?

Obviously, the RGCs can tell us plenty, from helping to confirm a glaucoma diagnosis to detecting a systemic condition and giving a patient with NAAION an earlier prognosis. Are you ready to listen?

References:

Spaide RF. Unsuspected central vision decrease from macular ganglion cell loss after posterior segment surgery. Retina. 2022;42(5):867-876. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000003408

Levin LA. Retinal ganglion cells and neuroprotection for glaucoma. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48(suppl 1):S21-S24. doi:10.1016/s0039-6257(03)00007-9

Chen JJ, Kardon RH. Avoiding clinical misinterpretation and artifacts of optical coherence tomography analysis of the optic nerve, retinal nerve fiber layer, and ganglion cell layer. J Neuroophthalmol. 2016;36(4):417-438. doi:10.1097/WNO.0000000000000422

Hood DC, Raza AS, de Moraes CG, Liebmann JM, Ritch R. Glaucomatous damage of the macula. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2013;32:1-21. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2012.08.003

Lee J, Kim YK, Ha A, et al. Temporal raphe sign for discrimination of glaucoma from optic neuropathy in eyes with macular ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer thinning. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(8):1131-1139. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.12.031

Tsamis E, LaBruna S, Leshno A, DeMoraes CG, Hood D. Detection of early glaucomatous damage: performance of summary statistics from optical coherence tomography and perimetry. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2022;11(3):36. doi:10.1167/tvst.11.3.36

Lee IH, Miller NR, Zan E, et al. Visual defects in patients with pituitary adenomas: the myth of bitemporal hemianopsia. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;205(5):W512-W518. doi:10.2214/AJR.15.14527

Smith EE, Saposnik G, Biessels GJ, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention, Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology, Council on Hypertension. Prevention of stroke in patients with silent cerebrovascular disease: a scientific Statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2017;48(2):e44-e71. doi:10.1161/STR.0000000000000116

Gupta A, Giambrone AE, Gialdini G, et al. Silent brain infarction and risk of future stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2016;47(3):719-725. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.011889

Jiang J, Wang Z, Chen Y, Li A, Sun C, Sun X. Patterns of retinal ganglion cell damage in nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy assessed by swept-source optical coherence tomography. J Neuroophthalmol. 2021;41(1):37-47. doi:10.1097/WNO.0000000000001025

Gonul S, Koktekir BE, Bakbak B, Gedik S. Comparison of the ganglion cell complex and retinal nerve fibre layer measurements using Fourier domain optical coherence tomography to detect ganglion cell loss in non-arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013;97(8):1045-1050. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-303438

Hayreh SS, Zimmerman B. Visual field abnormalities in nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy: their pattern and prevalence at initial examination. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123(11):1554-1562. doi:10.1001/archopht.123.11.1554

Kupersmith MJ, Garvin MK, Wang JK, Durbin M, Kardon R. Retinal ganglion cell layer thinning within one month of presentation for non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57(8):3588-3593. doi:10.1167/iovs.15-18736

Akbari M, Abdi P, Fard MA, et al. Retinal ganglion cell loss precedes retinal nerve fiber thinning in nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. J Neuroophthalmol. 2016;36(2):141-146. doi:10.1097/WNO.0000000000000345

Erlich-Malona N, Mendoza-Santiesteban CE, Hedges TR 3rd, Patel N, Monaco C, Cole E. Distinguishing ischaemic optic neuropathy from optic neuritis by ganglion cell analysis. Acta Ophthalmol. 2016;94(8):e721-e726. doi:10.1111/aos.13128

Toosy AT, Mason DF, Miller DH. Optic neuritis. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(1):83-99. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70259-X

Abel A, McClelland C, Lee MS. Critical review: typical and atypical optic neuritis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2019;64(6):770-779. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2019.06.001

Chen JJ, Pittock SJ, Flanagan EP, Lennon VA, Bhatti MT. Optic neuritis in the era of biomarkers. Surv Ophthalmol. 2020;65(1):12-17. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2019.08.001

Britze J, Pihl-Jensen G, Frederiksen JL. Retinal ganglion cell analysis in multiple sclerosis and optic neuritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol. 2017;264(9):1837-1853. doi:10.1007/s00415-017-8531-y

Articles in this issue

about 1 month ago

Managing glaucoma in an ophthalmic practice: An artful approachabout 2 months ago

“Family business?” Navigating the business of treating familyabout 2 months ago

Ortho-k: More than meets the eye to control myopia progressionabout 2 months ago

How to put wearable virtual reality technology to work in your practice2 months ago

The A to Zzzs of ocular health2 months ago

The microbiome in diabetes and DRNewsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.