- Vol. 10 No. 10

- Volume 10

- Issue 10

Visual haze leads to diagnosing unknown corneal dystrophy

Editor's Note: This case report is part of a series by members of Intrepid Eye Society.

Corneal dystrophies are often inherited, bilateral, and progressive disorders in which abnormal material collects in the layers of the corneal structure. Accurate diagnosis of corneal dystrophies can be difficult due to their rarity and variable clinical presentation.

Valuable factors that can aid in proper diagnosis include:

• The patient’s family history

• Pinpointing which layers of the cornea are affected

• The clinical characteristics of the corneal deposits/opacities

Case report

A new 56-year-old white male presented with a chief complaint of gradually increasing visual haze over the past 10 years in both eyes.

The patient reported being diagnosed with an unknown corneal dystrophy for which he had undergone two previous phototherapeutic keratectomy (PTK) procedures in his left eye.

He also reported that his mother, brother, and possibly his maternal grandfather have had bilateral corneal abnormalities.

The patient’s medical history was significant for hyperlipidemia that was well controlled with simvastatin (Zocor, Merck).

Clinical findings included best-corrected visual acuities (BCVA) of 20/25 OD and 20/50 OS with entrance testing results within normal limits.

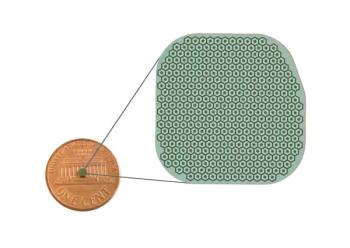

Upon biomicroscopic evaluation, corneal findings were significant for dense arcus 360 degrees, central stromal haze, and crystallization at the level of the epithelium/anterior stroma (Figure 1).

Dilated fundus exam yielded unremarkable posterior segment findings.

Anterior segment optical coherence tomography (OCT) revealed subepithelial hyper-reflectivity that correlates to areas of corneal crystallization (Figure 2).

Corneal topography indicated diffuse corneal irregularity and distortion in both eyes.

Pachymetry measured 589 µm and 346 µm OD and OS, respectively. The thin pachymetry reading OS is likely due to two previous PTK procedures.

Corneal sensitivity with cotton wisp revealed no intact sensitivity in the right eye and intact, but low sensitivity, in the left eye.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnoses with similar crystalline corneal findings that needed to be considered when diagnosing this patient included the following:1

• Fluoroquinolone/chlorpromazine use. This patient had no history of using these medications, excluding this as a diagnosis.2

• Bietti crystalline dystrophy. Bietti crystalline dystrophy is a rare, autosomal recessive disorder accompanied by retinal disease that causes progressive night blindness.3 This patient had unremarkable posterior segment findings, ruling out this diagnosis.

• Cystinosis. Often, cystinosis results in kidney failure at an early age.4 This patient had no known kidney problems, making a diagnosis of cystinosis highly unlikely.

• Infectious crystalline keratopathy. Microbial in etiology, infectious crystalline keratopathy typically causes a branching crystalline pattern, which was not present in this patient.5

• Lymphoproliferative disorders (monoclonal gammopathy, multiple myeloma). These conditions can rarely result in corneal findings, but the patient would have a history of bone pain, multiple bone fractures, or bruising.6 This patient did not have these symptoms.

Diagnosis

After careful consideration, this patient was diagnosed with Schnyder corneal dystrophy (SCD) based upon clinical presentation and family history with autosomal dominant inheritance pattern.

SCD is a rare and autosomal dominant condition. This dystrophy is rooted in an inherited mutation of the UBIAD1 gene that is involved in the local metabolism of cholesterol within the corneal environment.7

It is hypothesized that mutation of the UBIAD1 gene causes overproduction of cholesterol within the cornea.8,9

Therefore, by age 40, SCD patients typically present with dense corneal arcus, stromal haze, and corneal crystallization at the subepithelial layer.7,10

Clinical presentation of SCD has been found to be predictable by patient age. It is important to note that at any point in SCD progression, corneal crystals may or may not be present because only about 54 percent of SCD patients have been found to present with subepithelial crystals.7,11

Typical corneal findings of SCD based upon patient age:7

• <23 years old: Central stromal haze (with or without crystals)

• 23–39 years old: Central stromal haze and arcus (with or without crystals)

• >39 years old: Central stromal haze, arcus, and midperipheral panstromal haze (with or without crystals)

Along with these hallmark corneal findings, visual acuity and corneal sensitivity tend to decrease with SCD progression.7,12

Treatment

There is no available treatment to stop the progression of SCD.

Although penetrating keratoplasty (PKP) and deep anterior lamellar keratectomy (DALK) can be successfully performed in these patients, SCD can recur within the corneal graft.7,10

Patients should be referred for PTK as needed to remove subepithelial crystals that may be causing bothersome glare.13

Due to the diffuse corneal irregularity often seen in SCD patients, scleral contact lenses often allow for best acuity.

Genetic counseling is warranted because SCD is an autosomal dominant condition that can easily be passed on to offspring.7

Conclusion

Because SCDis very rare and may present in a variety of ways, it can be easily misdiagnosed or even overlooked in its early stages.

While crystalline deposits are often thought to be one of the landmark clinical findings for patients with SCD, only about half of cases present with them.

It is important to understand the various presentations to properly educate, manage, and appropriately refer SCD patients as the dystrophy progresses.

References:

1. Weiss JS, Khemichian AJ. Differential diagnosis of Schnyder corneal dystrophy. Dev Ophthalmol. 2011;48:67-6.

2. Siddall JR. The ocular toxic findings with prolonged and high dosage chlorpromazine intake. Arch Ophthalmol. 1965 Oct;74(4):460-464.

3. Sahu DK, Rawoof AB. Bietti’s crystalline dystrophy. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2002;50(4):330-332.

4. Gahl WA, Kuehl EM, Iwata F, Lindblad A, Kaiser-Kupfer MI. Corneal crystals in nephropathic cystinosis: natural history and treatment with cysteamine eyedrops. Mol Genet Metab. 2000 Sep-Oct;71(1-2):100-20.

5. Meisler DM, Langston RH, Naab TJ, Aaby AA, McMahon JT, Tubbs RR. Infectious crystalline keratopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1984 Mar;97(3):337-43.

6. Orellana J, Friedman AH. Ocular manifestations of multiple myeloma, Waldenström's macroglobulinemia and benign monoclonal gammopathy. Surv Ophthalmol. 1981 Nov-Dec;26(3):157-69.

7. Weiss JS. K The Oskar Fehr Lecture. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2016 Jun;233(6):708-12.

8. Yellore VS, Khan MA, Bourla N, Rayner SA, Chen MC, Sonmez B, Momi RS, Sampat KM, Gorin MB, Aldave AJ. Identification of mutations in UBIAD1 following exclusion of coding mutations in the chromosome 1p36 locus for Schnyder crystalline corneal dystrophy. Mol Vis. 2007;13:1777-82.

9. Nickerson ML, Kostiha BN, Brandt W, Fredericks W, Xu KP, Yu FS, Gold B, Chodosh J, Goldberg M, Lu DW, Yamada M, Tervo TM, Grutzmacher R, Croasdale C, Hoeltzenbein M, Sutphin J, Malkowicz SB, Wessjohann L, Kruth HS, Dean M, Weiss JS. UBIAD1 mutation alters a mitochondrial prenyltransferase to cause Schnyder corneal dystrophy. PLoS One 2010 May 21;5(5):e10760.

10. Weiss JS. Schnyder corneal dystrophy. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2009 Jul;20(4):292-8.

11. Arnold-Wörner N, Goldblum D, Miserez AR, Flammer J, Meyer P. Clinical and pathological features of a non-crystalline form of Schnyder corneal dystrophy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2012 Aug;250(8):1241-3.

12. Weiss JS. Visual morbidity in thirty-four families with Schnyder crystalline corneal dystrophy (an American Ophthalmological Society thesis). Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2007;105:616-48.

13. Paparo LG, Rapuano CJ, Raber IM, Grewal S, Cohen EJ, Laibson PR. Phototherapeutic keratectomy for Schnyder’s crystalline corneal dystrophy. Cornea. 2000 May;19(3):343-7.

Articles in this issue

over 7 years ago

How to diagnose a swollen optic nerveover 7 years ago

Proliferative retinopathy leads to risk of sight lossover 7 years ago

Hidradenitis suppurativa masquerades as blepharitisover 7 years ago

Know the legal aspects of myopia controlover 7 years ago

Support NEI research with eye bondsover 7 years ago

Applying precision medication to glaucoma and genomicsover 7 years ago

How air pollution affects the ocular surfaceover 7 years ago

Q&A: Casablanca, dry eye, and throwing axesover 7 years ago

How to know if a professional employer organization can help youover 7 years ago

ODs protest university name changeNewsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.