- July/August digital edition 2025

- Volume 17

- Issue 04

First, next, last: Timing of specialty lenses for patients with keratoconus

Calista Ming, OD, FAAO, FSLS, provides 3 cases of how to fit specialty lenses at the right time for patients.

When it comes to treating patients with keratoconus, there is no cookie-cutter solution. We must consider each patient’s needs and address both visual rehabilitation and corneal stability. Sometimes that means I fit them in scleral lenses immediately, and sometimes I postpone a new fit until after cross-linking. Regardless, contact lenses should not come at the expense of addressing the underlying disease process. Here are 3 cases that illustrate this process.

Case 1

The first is a woman in her early 30s. She had been seen elsewhere and fit in scleral lenses several years ago. However, they were no longer providing her with good vision, most likely because the keratoconus had progressed. We need to watch out for patients who may have been fit years ago with scleral lenses but have never undergone cross-linking. Such patients should always be evaluated and referred for treatment if the disease progresses.

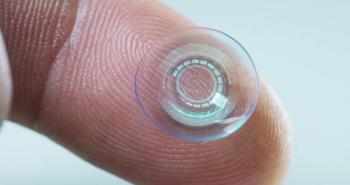

In this case, my patient had only count fingers (CF) vision without her lenses. The patient’s top priority was to be able to see again because her vision was so compromised. I explained that halting the disease with cross-linking would help stabilize her vision, allowing her to continue to use scleral lenses. I fit her in a new Zenlens scleral lens (Bausch + Lomb). This addressed her visual complaints and reduced her substantial visual disability. However, I also explained to her that she can’t just rely on scleral lenses because if the disease continues to progress, she may reach a point at which she can’t wear lenses and might need a corneal transplant.

I referred her to a cornea specialist for a cross-linking evaluation, explaining that iLink corneal cross-linking (Glaukos) could stop the keratoconus from progressing, although it couldn’t give her back the vision that was already lost. After cross-linking, she was able to resume wearing the same scleral lens I had fit her in before the procedure. However, because going without her lens before and after cross-linking was so onerous for her—she couldn’t work or drive—we had to plan carefully for the second eye surgery. With scleral lenses that vault over the cornea, the time out of lenses after cross-linking can be minimized, in many cases to as little as one week. Still, I think this case illustrates why patients should be encouraged to cross-link early, before they have CF vision that complicates scheduling. Additionally, with future developments in noninvasive cross-linking, patients won’t have an epithelial defect, further speeding up post-cross-linking recovery.

Case 2

With another patient, a 15-year-old boy, I took a slightly different approach. He was a spectacle wearer who came in for an appointment because his vision had decreased in his right eye. He had 4.00 D of astigmatism, and his vision wasn’t correctable to 20/20 in that eye. However, his binocular vision was still good because the left eye was 20/15. Based on the astigmatism and keratometry, I strongly suspected keratoconus, which was confirmed by topography. Because of his young age, we were able to get him scheduled for cross-linking on the right eye quickly. Keratoconus in young patients can progress very rapidly, so treatment within 6 weeks of diagnosis is ideal for those under age 18.1 Although I did fit him with a scleral lens after cross-linking on the right eye, I know that he wears it part-time. This patient and his parents were very motivated to address the underlying disease; he was not motivated to wear contact lenses, since he had no prior experience with them and had acceptable vision without them. We continue to closely watch his left eye for any signs of progression in that eye, which would warrant a prompt referral for cross-linking.

Case 3

A third patient had frank keratoconus in both eyes. We staggered the needed vision and corneal stabilization procedures, beginning with cross-linking in the worse eye, then fitting new scleral lenses for both eyes, and finally scheduling cross-linking on the second eye. After cross-linking, one of the scleral lens prescriptions needed to be changed by about 0.50 D to improve his vision. This approach helped to minimize the patient’s time off work by giving him reasonably good vision in at least one eye at all times. However, good education is crucial to ensure patients follow through with the cross-linking as planned. In my experience, patients delay making or cancel appointments for any number of reasons, including fear, misunderstanding, insurance changes, or a lack of education that leads them to not take the disease seriously. Sometimes it is just that other life events get in the way.

Scleral lenses and cross-linking work together

I always tell patients we don’t have a choice of one or the other: Scleral lenses and cross-linking go hand in hand. The scleral lens helps them see better; however, it isn’t going to stop the progression of keratoconus. For that, we need to stabilize the cornea with cross-linking. In planning for both treatments, we must factor in the patient’s school or work schedule, starting vision, insurance situation, and ability to manage out-of-pocket costs.

Too often, I see patients who have been told for years that they might have keratoconus but whose doctors never referred them to a specialist. By the time they get to me, these patients are often frustrated and have lost trust in the medical system. Their academic or professional success may have been negatively affected by poor vision, which can have lasting impacts.

I encourage doctors who don’t fit scleral lenses or have topography/tomography in the office to investigate where they can refer patients who may have keratoconus—or those with high-cylinder, increasing astigmatism, and/or reduced vision that can’t be explained. The National Keratoconus Foundation (nkcf.org), Scleral Lens Education Society (ScleralLens.org), and Glaukos’ OD education site (iDetectives.com) all have provider locaters on their websites, and the latter also features clues to help identify patients who may have keratoconus and an artificial intelligence detective chatbot. Referring patients to optometrists who specialize in scleral lenses and ophthalmologists who perform cross-linking can ensure your patients get a formal diagnosis and start down the path to cross-linking while they still have good vision.

Reference:

Romano V, Vinciguerra R, Arbabi EM, et al. Progression of keratoconus in patients while awaiting corneal cross-linking: a prospective clinical study. J Refract Surg. 2018;34(3):177-180. doi:10.3928/1081597X-20180104-01

Articles in this issue

5 months ago

Myopia is an escalating global health crisis5 months ago

Inside genetics and glaucoma6 months ago

Embracing dry eye6 months ago

A case of orthokeratology for high myopiaNewsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.