- September/October digital edition 2025

- Volume 17

- Issue 05

Multidisciplinary collaboration achieves optimal outcomes for patients with dry eye

Transforming care by integrating systemic, ocular, and emotional health can deliver personalized treatment and better outcomes.

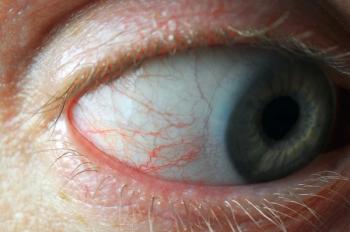

Dry eye disease (DED) is no longer viewed as a simple problem of insufficient tearsor ocular irritation. It is now understood as a multifactorial, multisystemic condition involving inflammation, tear film instability, neurosensory disruption, and a host of systemic contributors.¹ These overlapping mechanisms rarely act in isolation, so managing DED often requires a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach.

Patients frequently present with burning, stinging, fluctuating vision, and asthenopia, yet objective clinical signs may be minimal or absent. Conversely, significant staining or meibomian gland dropout may be present even without symptoms.² This well-known disconnect underscores the need to assess DED in a broader context that accounts for systemic health, neurologic input, hormonal balance, and emotional well-being.

Medical collaboration

Autoimmune disease is a prime example of how systemic health plays a central role in DED. A patient presenting with dry eye and vague systemic complaints, joint pain, or fatigue may be in the early stages of Sjögren syndrome. Without collaboration with a rheumatologist, diagnosis and treatment could be delayed for years, with progressive ocular and systemic damage in the meantime.³

Similarly, dermatologic conditions like rosacea and seborrheic dermatitis are tightly linked to meibomian gland dysfunction.⁴ Patients with these conditions often benefit from dermatologic interventions targeting inflammation that affects both the skin and eyelids. In cases of lid margin disease, collaborative management can prevent chronic flare-ups and accelerate recovery.

The role of hormonal health

Hormonal factors also may play a role. Estrogen and androgen receptors are present throughout the ocular surface and adnexa.⁵ Androgen deficiency can lead to reduced meibum secretion and increased inflammation, whereas estrogen fluctuations may destabilize the tear film.⁶ These effects are especially relevant in menopause, pregnancy, or with oral contraceptive use. In these contexts, collaboration with appropriate medical practitioners can offer additional insight or support.

Addressing emotional and neuropathic factors

DED’s impact on quality of life is often underestimated. Studies have shown that the burden of dry eye can rival that of mild angina or kidney failure.⁷ Patients may experience social withdrawal, frustration, or even depression due to persistent discomfort and visual fluctuation.⁸ Behavioral health support can be a useful component of care, helping address the disease’s emotional toll and improving adherence.

Neuropathic pain adds another layer of complexity. Patients with burning, photophobia, or discomfort out of proportion to clinical signs may be experiencing corneal nerve dysfunction, rather than classic tear deficiency.⁹ Such patients may benefit from referrals to neurology or pain specialists, especially when dry eye overlaps with migraine, fibromyalgia, or postviral syndromes. Tools like in vivo confocal microscopy help identify these problems and personalize care accordingly.

Sleep disorders and psychoactive medications

Sleep disorders and psychiatric medications can also intersect with dry eye. Medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or antihistamines can reduce tear production or alter blink dynamics. Obstructive sleep apnea, which is often linked to floppy eyelid syndrome, increases the risk of mechanical trauma and inflammation during sleep.¹⁰ Working with prescribing physicians or sleep specialists can prevent ongoing damage and improve morning symptoms.

Interdisciplinary surgical comanagement

Even within eye care, collaboration is key. Although optometrists often lead the charge in diagnosing and managing DED, including performing procedures like intense pulsed light therapy (a light-based treatment that targets meibomian gland dysfunction), thermal gland expression, punctal occlusion, and scleral lens fitting, ophthalmologists also play a vital role, particularly in advanced or surgical cases.¹¹ Preoperative ocular surface optimization before cataract or refractive surgery can significantly improve visual outcomes and patient satisfaction. Close communication among providers ensures that patients receive comprehensive care without redundancy. Sharing records, clinical findings, and treatment goals allows smooth transitions between specialties and supports long-term success.¹2

Creating a collaborative framework

To avoid sporadic or fragmented referrals, it is important to establish intentional, ongoing relationships with medical and behavioral health professionals. Educating collaborators on ocular manifestations of systemic conditions, and vice versa, can lead to more effective and timely interventions. Including meibography or osmolarity results in referral notes can guide other clinicians toward relevant diagnostic workups.

We now see the emergence of dedicated dry eye centers where multiple specialties work side by side, whether physically colocated or through virtual collaborations. E-consults can be especially useful; sharing test results and imaging with a medical practitioner can speed up diagnosis and minimize unnecessary delays.

Technology also plays a growing role. Artificial intelligence–driven platforms and digital tools can help track symptom trends, flag risk factors like polypharmacy or incomplete blinking, and tailor treatment pathways for each patient. Shared decision-making helps reduce guesswork in long-term care.

Empowering the patient

Perhaps most important is involving the patient as an active member of the care team. When patients understand how their hormones, medications, diet, and behaviors impact their eye health, they are more likely to stay engaged with treatment. Tools like digital symptom trackers, blink training apps, and care maps can empower patients to bring meaningful observations to each visit.

Interdisciplinary education, whether it is a pharmacist clarifying adverse effects of medication, an occupational therapist offering ergonomic strategies, or a clinician empowering patients to improve their diet and incorporate ω-3s, can enhance comfort and adherence.

Conclusion: A networked approach to a networked disease

Dry eye is not just a local ocular issue, but a reflection of broader systemic and lifestyle factors. As such, its management must be just as comprehensive. Through communication, collaborative care, shared data, and mutual education, we can improve clinical outcomes and quality of life.

As care models evolve, we must also advocate for systemic support that recognizes the time, effort, and value of multidisciplinary coordination. When providers across disciplines work together, we can offer patients a personalized and integrative care pathway.

References:

Craig JP, Nichols KK, Akpek EK, et al. TFOS DEWS II Definition and Classification Report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):276-283. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.008

Stapleton F, Alves M, Bunya VY, et al. TFOS DEWS II Epidemiology Report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):334-365. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.003

Daniels TE. Labial salivary gland biopsy in Sjögren’s syndrome: assessment as a diagnostic criterion in 362 suspected cases. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27(2):147-156. doi:10.1002/art.1780270205

Lemp MA, Crews LA, Bron AJ, Foulks GN, Sullivan BD. Distribution of aqueous-deficient and evaporative dry eye in a clinic-based patient cohort: a retrospective study. Cornea. 2012;31(5):472-478. doi:10.1097/ICO.0b013e318225415a

Sullivan DA, Rocha EM, Aragona P, et al. TFOS DEWS II Sex, Gender, and Hormones Report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):284-333. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2017.04.001

Versura P, Campos EC. Menopause and dry eye: a possible relationship. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2005;20(5):289-298. doi:10.1080/09513590400027257

Mertzanis P, Abetz L, Rajagopalan K, et al. The relative burden of dry eye in patients’ lives: comparisons to a U.S. normative sample. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(1):46-50. doi:10.1167/iovs.03-0915

Miljanović B, Dana R, Sullivan DA, Schaumberg DA. Impact of dry eye syndrome on vision-related quality of life. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143(3):409-415. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2006.11.060

Galor A, Levitt RC, Felix ER, Martin ER, Sarantopoulos CD. Neuropathic ocular pain: an important yet underevaluated feature of dry eye. Eye (Lond). 2015;29(3):301-312. doi:10.1038/eye.2014.263

McMonnies CW. The potential role of sleep and mood in dry eye symptoms. Optom Vis Sci. 2011;88(9):E1209-E1216.

Syed ZA. Comanagement in dry eye disease: why we should consider managing DED patients with optometrists, and how to make this model work. Ophthalmol Manag. 2023;27(April):42,44.

Wolffsohn JS, Craig JP, Jones L. An action plan for managing dry eye. Review of Optometry. Published online May 15, 2024. https://www.reviewofoptometry.com/article/an-action-plan-for-managing-dry-eye

Articles in this issue

Newsletter

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to Optometry Times and get clinical pearls and practice tips delivered straight to your inbox.